Galtung's triangle of violence - a model for understanding social conflicts

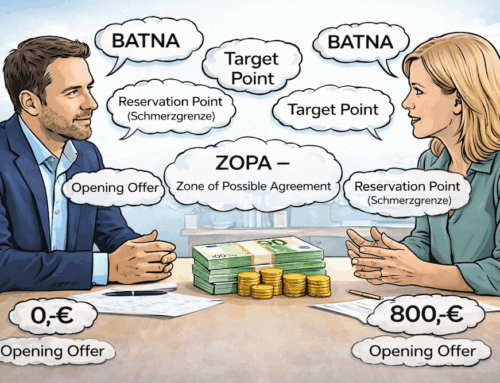

In terms of methodology, mediation is based on the idea that conflicts can be resolved by clarifying and reconciling the hidden Interests can be solved. "Hidden" are the interests in or behind the Positionswhich (must) be taken in (verbal) combat.

However, as long as the parties are not prepared, for whatever reason, to discuss their interests together, but to fight each other outright or even against the rules, constructive conflict management requires a good understanding of the dynamics underlying the fighting, warring and outbreaks of violence. Johan Galtung's triangle of violence is a helpful and tried and tested model of forms of violence.

We can still "experience" in the daily news that violence and war are often the decisive methods of conflict resolution, especially in international relations. And yet; this "still" is an expression of historically justifiable optimism, because this violence has steadily declined relative to the population! Whether this decline will continue is an open question, but there is much to suggest that it will. In fact, the incidence of violence is falling, and state-initiated violence is also steadily decreasing and becoming more and more limited. Even if it does not currently appear that violent conflicts and violence are generally on the decline, this is nevertheless the case. Our news-driven understanding of such phenomena may find this difficult to comprehend, but it is also based on an extremely limited time horizon and mental horizon.

Nevertheless, war and interstate violence remain an acute and global problem that the Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtunga founder of international peace and conflict research. This blog post will focus on him and the conflict resolution model he developed in the late 1960s. This model deals with the emergence and dynamics of international conflicts and various forms of violence.

Johan Galtung at the Second Joint Mediation Congress in Ludwigsburg 2014

In his triangle of violence, Galtung describes the Main aspects of a conflict as attitudes, behaviours and contradictions. The model was originally intended for use in war situations, but it can also be applied to other types of conflict, such as violence in families and discrimination of all kinds.

Attitudes, Behaviour and Contradiction

In Galtung's triangle of violence, the three elements attitudes, behaviour and contradiction combine to form a consistent model that aims to make the existing interactions comprehensible.

Attitudes describe the part of the conflict that is fuelled by assumptions, perceptions and emotions that one party to the conflict may have about the other. A particularly significant source of escalation in emerging conflicts, for example, is the lack of endeavour to show understanding for the other side, to believe that they have good or at least understandable motives. Instead, the motives are inferred from the negative effects, which of course also (have to) appear negative in this light. This is simple, but above all "logical" and therefore "correct". Thinking and assessing from several, even initially contradictory, perspectives is therefore an important skill when analysing conflicts. Ultimately, it is not the perspectives that contradict each other, but the conclusions that can be drawn from these perspectives. Of course, these conclusions are our work, we can influence them and therefore also reach them differently. According to Galtung, attitudes are responsible for "cultural violence".

Behaviours describe the part of the conflict through which the conflict becomes perceptible and tangible, characterising its verbal and physical expression. They are visible and, according to Galtung, responsible for "direct violence".

Contradictions are ultimately the actual cause of the conflict: they stand for the collisions between the conflicting parties, which are perceived by both sides and actually led to the conflict in the first place. For Galtung, the contradiction is therefore the root of the conflict, it causes the violent behaviours. According to Galtung, contradictions are often rooted in structural violence.

Forms of violence - cultural, structural and direct violence

In addition to the three core concepts of attitude, behaviour and contradiction, Galtung focuses on the concepts of cultural, structural and direct violence in his model in order to find approaches for conflict resolution. He comments on this as follows:

"The visible effects of direct violence are well known: The killed, the wounded, the displaced, the material damage, all increasingly affecting the civilian population. But the invisible effects may be even more diabolical: Direct violence perpetuates structural and cultural violence."

(Johann Galtung: Violence, War, and Their Impact: On Visible and Invisible Effects of Violence, Polylog: Forum for Intercultural Philosophy 5, 2004; translation by the author).

Galtung differentiates between three forms of violence.

Direct violence is exercised by a specific actor and is observable. Direct violence flares up in physical and verbal forms, is relevant under criminal law and is subject to justification. Classic direct acts of violence are killing, beatings, torture or rape. However, insulting or otherwise belittling others is now also a recognised form of direct violence. According to Galtung, the reasons for the emergence of direct violence lie in the existence of structural and cultural violence.

Galtung's conception corresponds to the idea that such violence does not represent the conflict as such, but attempts to resolve conflicts, albeit in inglorious or reprehensible ways.

Structural violence must be distinguished from direct violence in that it does not originate from a specific actor. Structural violence, for example, is not directly attributable or therefore not "measurable" under criminal law. Rather, it manifests itself in social and global...well...how else can it be described...than tautologically...structures, norms and values. Structural violence manifests itself, for example, in unequal educational opportunities, in differently restricted opportunities for political participation and legal disadvantages for certain population groups. Structural violence is also recognisable in the restricted access to goods and resources of certain population groups. Structural violence exists when these inequalities are inherent to the social, political and economic systems, are systematically evident and at the same time are rooted in them.

Exemplary The measurable fact that the poor are "more likely" to die than the rich is a sign of structural violence. This is not necessarily evident in individual cases ("And what good was his wealth?! Nothing, the cancer still killed him...!) But it is clearly evident in the "big picture". But this can only be realised with Statistics adequately. And we all know the pejorative reactions when this is mentioned).

Cultural violence in turn is fed by the attitudes of individuals and their dynamics in groups and societies. Individual attitudes arise decisively in the context of the individual, but socially framed socialisation of all. According to Galtung, socialisation gives rise to conflicts between the self and the other. This can result in aspects of culture such as religion, language or science being instrumentalised to justify the existence of direct violence. Adaptation processes are violently supported. From this sociological perspective, cultural violence means that we are unaware of factors that prevent us from recognising or at least justifying direct and structural violence.

At this point, the debate may arise as to whether any form of violence can be prevented or should at least be undesirable. This is because these definitions take us quite far into the realm of ideological trench warfare (parenting methods, ideas of order, etc.) and we could quickly be tempted to throw out the entire topic. That would be a real shame and would not only mean throwing out the proverbial baby with the bathwater, but also throwing out the whole tub. Then we would really be stuck in the mud of violence.

We really cannot yet imagine a world in which all violence is outlawed and refrained from. Too strange and almost utopian is what is trying to form a consistent picture in our heads. But it seemed to many of us not so long ago completely absurdthat it should be socially ostracised and forbidden by the state to beat your own children "to get them off to a good start". And perhaps some readers are still wondering whether this is really true with regard to the criminal law prohibition. After all, it doesn't just mean the nice idea from a child's perspective that "I must not be beaten". It also means the not-so-nice idea from the adult perspective that "my child is allowed to use force to prevent me from raising my hand". It can't go that far, can it? Well, children and young people are also entitled - in line with the ban - to Right of self-defence according to § 32 StGB against the parents to.

In any case, Galtung's model makes it clear that direct violence is the most obvious form of violence. This is why it can be identified and combated most quickly. Structural violence, on the other hand, is usually not recognisable at first glance, as it does not reveal a direct actor (perpetrator, culprit). These two factors can mean that both structural and cultural violence are highly dangerous = influential, as they operate below the social radar and may evade social debates and "conscious change processes".

All forms of violence are mutually dependent on each other. According to Galtung structural violence leads to direct violence and can be justified by cultural violence. All forms of violence interact with each other in a dynamic process. If one of the forms of violence is missing, there is no open conflict, but rather a latent conflict.

Solution approaches

Due to our current level of abstraction, the possible solutions can only be outlined here.

Direct violence can be combated because the specific behaviour serves as a point of reference. This is due to peace-keeping processes possible. This is referred to as negative peace, as it involves the absence of direct violence. The legal system and its enforcement serves the absence of violence, creates security and order.

To structural violence structural contradictions must be combated. This is achieved by peace-building processes possible. If this is promising, we speak of positive peace, as it is not just about the absence of direct violence, but about the absence of structural violence in all areas of society.

To cultural violence attitudes need to be changed. Here one speaks of peace-making processes. This is also referred to as positive peace. It is about creating equal power relations that are strong enough to avoid future conflicts. In European history, there is certainly optimistic experience with this kind of balance of power, which is reflected in the constitutional formula of the checks and balances have already made their voice heard. The Constructive dialogue Peace-making plays a decisive role by reaching agreements within a society or between conflicting parties on issues that have previously led to conflict. The aim of peace-making is to achieve reconciliation and mutual understanding.

This subheading includes the Mediationwhich, as a conflict management process, enables peace-making agreements that may emerge in the dialogues and cooperative negotiation processes.

Summary

According to Galtung, conflicts can have positive effects if they lead to social change and thus to positive peace. Whether this happens depends on whether constructive conflict management or a Conflict transformation that lead to viable solutions.

This can also be applied to the Mediation transfer: the attitude is the starting point here. A discussion in the form of a dialogue can lead to the structural background (contradiction) of the conflict being changed. This in turn can lead to a change in the behaviour of the conflict parties and thus transform the conflict on all three levels. So much for Galtung's theory, which he developed from his practical experience with international conflicts and crises.

Leave A Comment