The authenticity revolution

Postmodern areas of tension in the idea of self-realisation

Cultural sociological insights and concepts according to Andreas Reckwitz

I. Introduction

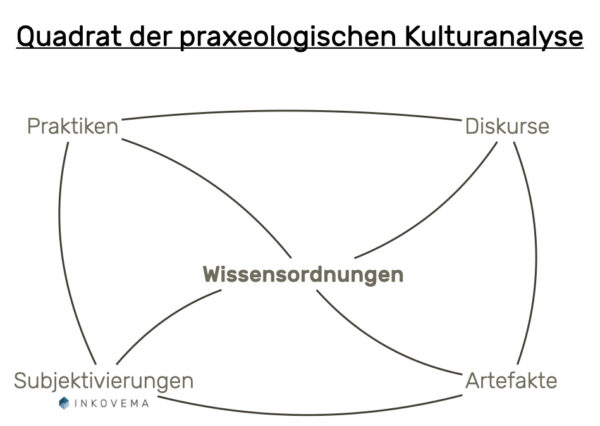

By way of singularisation and culturalisation, postmodernism (from around the 1970s) displaces organised modernity as it had developed in the USA and Western Europe since the 1920s. This singularisation noted by Reckwitz can be seen in five units – namely in objects (artefacts, especially objects), in subjects, in spaces (places, cities, natural areas etc.) as well as in temporalities (events etc.) and in collectives. They are activated and claimed by social practices.

Reckwitz emphasises three drivers of singularisation: the socio-cultural authenticity revolution, the post-industrial cultural capitalism revolution and the mathematical-technological digital revolution. The following is about the socio-cultural authenticity revolution.

II The academic middle class – carrier of the authenticity revolution

The socio-cultural authenticity revolution is being driven by the academic middle class, which initially made up only 5% of the population in the 1960s, but now accounts for over 30% in all western industrialised countries. In comparison, the industrial labour force, for example, has fallen from around 50% in almost all industrialised countries to around 20% of the workforce. Students are not an elitist fringe phenomenon, but have become - if you like - the "social norm". An educational explosion of unimaginable proportions. The rise of the academic middle class to become the socio-culturally defining class goes hand in hand with a fundamental change in lifestyle and life expectancy: While the employee (subject) in the organised modern age was still concerned with increasing the (normalised) Living standards, the postmodern subject is concerned with quality of life and an authentic lifestyle. The associated search for the individual, "real", one's own and actual life is now made possible and demanded from childhood onwards. The postmodern subject must live their best life if they do not want to feel the anxiety and shame of having missed this opportunity.

It is precisely this revolution of authenticity that summarises the much-vaunted change in values as if in a burning mirror and describes the shift from values of duty and acceptance to values of self-development. What are the roots of this cultural trend that has grown into cultural hegemony in the postmodern era?

II. Historical roots of the claim to authenticity

The ideas and socio-cultural strands lead to the Counter Cultures of the 1960s back to the Bohemian artistry at the turn of the centuryThe ideal image of the artist, who is always creative, sometimes chaotic, always self-centred and in this sense asocial in the upper and lower middle-class world of the late 19th century. And yet, it is precisely this type of artist that anticipates the subjective ideal of postmodernism, in which each and every one of us is profiled and presented in social media, understood across disciplines as creative and striving for freedom, be it in child and adult psychology, in education – and in the life and labour sciences anyway.

But the bohemians are themselves the heirs of the European Sturm und Drang movement, which followed on from the Romanticism of the 18th century, where the roots of the claim to authenticity go back to.

Romanticism corresponds to the logic of the particular (doing singularity) and was for a long time the less significant alternative to the logic of the general (rationality, formalisation, norm(alisation), standardisation, etc.). Socially, it was a marginal phenomenon, at home in art, especially painting and literature; something for enthusiasts, as amateurs used to be called, who practised the activity as a pastime but not as a serious profession.

For the singularisation processes that have taken over dominance in "Western cultures" since the 1970s, the culture of Romanticism should therefore not be overestimated. Romanticism is culturally the first radically singularising countermovement and strived for the "real", authentic life. It resisted the modernity of the general, its standardisations, normalisations and classifications, which were primarily carried out within the framework of Enlightenment philosophy and against the "equalising" and "organising" industrialisation of the mode of production and economy.

The romantic Speciality culture rather discovered the intrinsic complexity in everything, tested the "Re-enchantment of the world", which had desecrated the natural sciences. Romanticism was (and is) culturalisation and valorisation of the world, singularisation par excellence. But the valorisation of phenomena always goes hand in hand with the de-valorisation of other phenomena. And this by no means only applies to People ("creative artists", industrial workers), but also things and objects (consumer revolution in the 19th century!), temporalities (postmodern event culture) and spaces (dark Middle Ages, desecrated sciences, corrupting economy) as well as collectives (nations, people, foreigners). This is where cultural and valorisation struggles will later emerge.

III Claim to authenticity as the ideal of self-realisation

The decisive factor in this cultural "line" is the creation and significance of people's personal, above all emotional, inner world. It is declared to be unique, individual and therefore indivisible, to a certain extent also incommunicable, far removed from any functional logic, but nevertheless (increasingly) unfolding. The core drive of the Romantics, including the Sturm und Drang and the Bohemians, is the Development of the self. According to this world of ideas, life is – about becoming the person you are (basically, actually) meant to be, revitalising your true self; living your best life because you can, are allowed to – and ultimately owe it to yourself and others.

But one important aspect has changed in this cultural trajectory: The aspirations for self-actualisation in the postmodern world (from the 1960s onwards) are no longer directed against the world – and no longer need to. While counter-cultures still had to be directed against the social "establishment", cultural hegemony has since been taken over by (romantic) self-development values. In pedagogy and educational science, in the counselling and life sciences, the claim to the self-development of the individual is undisputed everywhere and is promoted and demanded. Self-realisation is free and self-chosen, but should be socially recognised. Originally, this SELF, which strives for its own, innermost self, was an invention of Romanticism, and was also identified by the humanistic psychologies of the 1950s and 1960s: Maslow's self-growth, self-realisation and self-actualisation or in Berne and his transactional analysis, in which the ultimate goal is autonomy.

Of secondary importance is whether this self-realisation takes the form of a much-vaunted Journey inwards in which the self is the subject of intensive self-exploration, whether in Zen, pilgrimage, handicrafts, reading or making music, or even in Aikido or lifelong therapy (urban neurotics).

Self-development can, however, also help the still underdeveloped self through A journey into the globalised world always in search of authentic, unfolding experiences. Self-realisation becomes performative. The subject not only finds itself, but becomes itself in dealing with the world. The individual practices have a valorising effect on the units of objects, time, space, collectives): I am worth it! Food must be ethically clean, friends politically correct, professions meaningful and valuable, holidays authentic and green, partnerships should be enriching and children should have experiences. Life is curated, performative, must be staged – social media profiles!

IV. Paradoxes and tensions

The postmodern self, fixated on authenticity, lives under inner tension. Of course, it is possible to try to resolve this tension with even more of the same, even more inwardness, even more travelling. But this in no way does justice to the scope of the problem. Because the paradox that the claim to authenticity entails is not taken into account.

Although the diagnosis that today it is hardly possible to really rebel against the old is not original, the paradox of postmodern claims to self-development is not yet fully clear: In the postmodern world, not only is it not the case that the subject no longer has to develop against society, this society even demands self-realisation always and everywhere and valorises – as I said – authenticity.

- Now it becomes tragic, because society observes, interprets and evaluates who and what is authentic and who and what is not. Authenticity is no longer the subject's self-assertion against an already normalised, standardised society, but (also) an attribution, so that efforts at authenticity can also be written off, are fake, affected, put on, false and bland.

- The postmodern subject is caught in an almost unsolvable double bind: It wants to be authentic, to do something out of itself, independent of social, familial norms and standards and yet, no, and therefore the recognition and to a certain extent ratification of society for this self-development. This is where two culturally and historically conflicting currents into a paradoxical symbiosis: On the one hand, the subject of the modern bourgeoisie, who often put personal desires aside in order to live conventionally and conscientiously, socially recognised, an adequate life.standard to achieve. On the other hand, the fate of the romantic subject, who often eked out an asocial existence on the fringes of society, but was able to experiment.

I will address these three factors of societal transformation in the next draft of the institute.

Leave A Comment