The concept of psychological games in transactional analysis

Part 4: Conflict counselling practice in the face of psychological games

Game invitations and termination options

The psychological games are a Concept of transactional analysiswhich deals with communicative patterns of a manipulative nature. These psychological games are usually destructive in nature. Eric Berne, the founder of transactional analysis, was instrumental in developing this concept. With his – one could say – bestseller „Games People Play“ (1964), he was instrumental in the early success of transactional analysis as a school of humanistic psychology.

In this fourth part of our short series of articles, we look at the connections in practice and their complex communication structures, which can be recognised, if not decoded, with the help of the game concept.

A short series of articles on the psychological games of transactional analysis:

Introduction

The concept of psychological games can be used not only for conflict counselling and mediation, but also for Conflict dynamics and – typical of a 20th century psychological concept – to uncover and ultimately „ free the participants from it“. According to TA theory, games are part of the life script from which the client must, if not free himself in therapy, then at least consciously and in full possession of his psychic powers take up a new position (new decision therapy according to Goulding). Ultimately, the TA revolutionaries „are also ok“ with adults doing what they have been taught by their parents, but this should be an autonomous, present decision rather than an approach adopted in childhood and now unconsciously adopted and practised. In this respect, transactional analysis strives to move from automatisms to human autonomy. In this respect, the The game concept can be used as a diagnostic and intervention concept for the underlying conflict.

In addition, the game concept can also be used by the mediator to make the mediation discussions themselves as game-free as possible. With the idea of a parallel process (in) mediation, this is also quite obvious. In other words, the assumption that in the mediative handling of the conflict, the same conflict will also emerge and establish itself in mediation, perhaps with different role allocations, but in principle identical. Here the Game concept as a diagnostic and intervention concept for the organisation of mediation discussions.

It is therefore important for mediators and counsellors to be able to recognise other people's game invitations and to have studied and kept an eye on their own susceptibility.

Important when dealing with psychological gamesthat it is hardly ever about the subject matter of the games themselves, but about the associated confirmations of life experiences and thus about the psychological safeguards of the „conclusions“ once reached. Games are, on the one hand, script confirmation events and, on the other, desperate attempts to make new experiences. It is therefore not worthwhile for conflict resolution to thematise, relativise or refute the specific content, but rather to approach the life issues and positions in a clever and respectful way. However, there is by no means always time, space and willingness for this in mediation.

1. game invitations

They open up the psychological game from the player's perspective, but they must also be accepted by the potential player. Otherwise the invitation fizzles out and „demands “ another invitation. In terms of transaction analysis, this is an ambiguous (trans)action. TA assumes that the psychological level of this ambiguous action and possibly transaction will determine the progress of the social interaction more intensively than the social level of the transaction.

The game-inviting (re-)action serves as a lure or trap, even though it regularly lacks the intentional moment. Game invitations are unconscious. Otherwise it is a manoeuvre, as Eric Berne put it.

Game invitations are not infrequently seen in any kind of devaluation or – in contrast – in exaggerations, so-called grandiosities. Both such exaggerations and devaluations are expressed transactionally with a negative basic attitude and thus from one of the role patterns of the drama triangle, as a saviour, victim or persecutor role.

Examples

- Starting a conversation between friends: "I just can't take it anymore with my boss!"

- Among friends, acquaintances, colleagues: "You have to say what's going on!";

- "This timidity in politics won't last much longer, they have to crack down much harder!"

- "It wouldn't have been like this in the past...!";

- "What a hothead, this new guy!";

- (unprompted): "If I were you, I wouldn't wear a pink shirt, other colours look much better on you...!" etc.

1. game invitations from the three drama corners

- Game invitations from the chasing pack...are reproving, belittling and reproachful, often out of the blue, unasked; sometimes just a groan, a frown or other statements that "provoke" clarifying questions...but where it is already apparent that there will be no clarification, but rather self-representations, accusations and self-righteousness.

- Game invitations from the saviour role:...are helpful and always well-intentioned, but unasked for, appear overbearing or patronising, saviour starts interfere in other people's affairs and also open them up. The game invitations from the saviour role are usually very welcome socially and difficult to recognise as escalating; their rejection resembles a slight scandal...

- Game invitations from the victim role...clumsiness, ignorant and submissive behaviour, overly shy, building up a pull, relying too much on the "conviction" that you have to help!

2. ...and the game beckons forever!

Game invitations attract complementary players, rescuers find victims, pursuers too. And victims find rescuers and persecutors too. And persecutors find victims – and usually other persecutors who initially came along as rescuers. Got mixed up? Well, that's exactly what characterises conflict dynamics in the drama triangle. But there is a bit of a Wild West atmosphere. Sometimes it feels as if you're at the mercy of others, but at the same time as if (you) are allowed to do a lot, if not everything... after all, you're only reacting and the other person is ultimately to blame. And the feeling of being on the right side of the value divide doesn't last long or degenerates because the price is simply too high. And just around the next communication corner lurks the realisation that the other person is also quick on the draw, also makes his moves and vigilance is paramount. And then you're right in the middle of it, in the next stage of escalation of the conflict.

If you don't recognise your susceptibility to gambling and have a loving grip on it, you will fall into the trap – especially in the mediator role of an escalated conflict that has found its way into mediation.

But be careful: not every conflict is a psychological game and its dynamics are no proof of the „existence“ of a drama triangle.

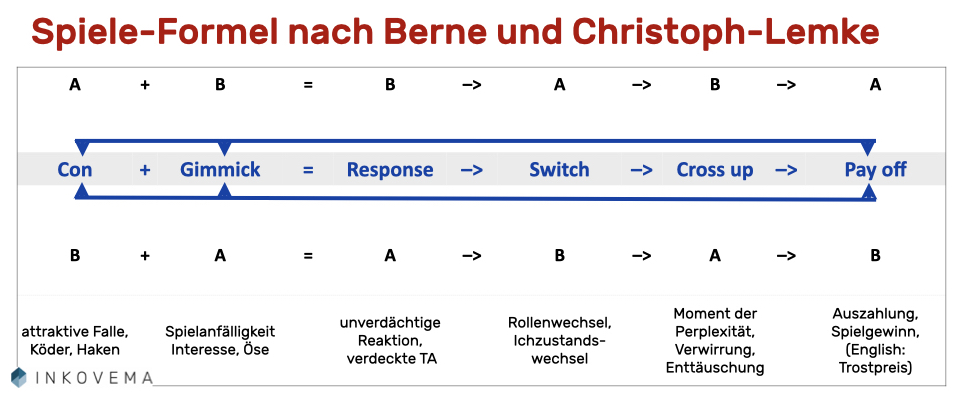

Game invitations configure the relationship and communication pattern and can lead to the popular snitching game of who started the drama triangle. But what Christoph-Lemke (1990) has worked out applies here: There are always at least two players, each with their own game – and therefore always two invitations. The search for the beginning, where the blame is assumed to lie, does not lead any further.

2. course of the game

It is typical of mediation that game invitations and moves always leave several options and that the role allocation is not conclusive or even unambiguous, but depends on the subsequent reactions. These are illustrated here by way of example.

Situation I: Two angry team members in mediation.

A bursts out in anger, coupled with a dash of self-righteousness:

A: "You can't work with B! The way he sometimes turns up for work and what happens then is just...outrageous/unbearable/abnormal etc.!"

B can react to this – in different ways with regard to the mediator –:

- B may be completely surprised or outraged by this. (Open question of clarification or demarcation, role clarity)

- Or B acts surprised or indignant or horrified at such outbursts – also with a view to the mediator (victim role)

- Or acts detached and knowing, because he knows this "old chestnut" (and rises above the complaint and indignation of the other, persecutor role)

Game invitation: The invitation to play takes the form of an unclear mixture of reproach (persecutor; "I'll show you’s! I won't put up with that…") and a description of suffering (victim, "Look, I have to work with him…!")

The reaction of the other player B and the reaction of the mediator M, as well as A's understanding of the reactions of B and M, determine the further course of events.

Situation II: Mediator asks specific questions.

Mediator e.g.: "From your point of view, what specifically happened..."?

(This question can be asked in a persecutory manner or even just arrive in a persecutory manner, even though it was meant to clarify and contribute to clarity. It is therefore not only the susceptibility of the mediator to play games that is important here, but also whether and to what extent he expects that he may be misunderstood and that this will have an equally dramatic influence on the progress).

possible susceptibility to play – saviour:

However, the demand or the acceptance of the assignment itself may already harbour the possibility of a willingness to rescue or even be assumed by the parties to the conflict. To exaggerate, the offer of mediation can already be (mis)interpreted as an invitation to play… because – if the world of the parties involved sees it that way – who would voluntarily engage in a conflict dialogue, especially one involving other parties?! This can be enough for a communicative victim-rescuer dynamic; the mediator doesn't even need to be explicitly drawn into concrete rescue attempts and, for example, develop ideas for solutions that are then all rejected...

Examples: for conflicts when working at a distance

...Have you already tried...? // ...You could...!"

- Utilise flexitime regulations

- Moving and getting out of the way

- Putting each other in the picture

The concept of psychological games is a good example of what can (unfortunately) happen when the mediator makes suggestions. With these TA glasses, suggestions appear to be rescue attempts that increase the confusion of the parties involved rather than contributing to clarification.

Irritations The mediator's expectations are also raised when the mediator indicates that this really is a difficult case and that he is coming to the end of his tether (victim). This is sometimes a new invitation to play a game in which the aim is to see who can score the most points with the mediator with constructive suggestions…(Of course, the mediator's communicated letting go – „I give up…!“ – can also be an effective, blockade-breaking intervention – and mediation „saves“ without causing damage).

3. match terminations

Psychological games can, of course, be played to the end, to the bitter end. The stages of the game can be turned up to the third degree and social relationships can suffer as a result. However, the following is about how Psychological games ended before or cancelled in the middle can be realised.

A staged procedure is available for this purpose.

Consciously ending psychological games

The first step is to consciously perceive and realise that a psychological game is being played here in the clarification process. This means that invitations are exchanged, invitations are accepted, psychological games are kept going or at least allowed to happen without confrontation. Consciously recognising these processes is a personal and important contribution to a „good ending“. This is usually not so easy and hardly possible without outside help. Supervision is therefore an important tool for mediators to ensure the quality of mediation.

1st concept: Drama triangle

In practice – also in mediation – the thinking model of the drama triangle helps with this step. The catchy depiction and dynamics between the three classic role models are quickly understood and can be transferred to your own life experience. The psychological trap usually consists of believing that you are the victim of others in the triangle and making the next move from this communicative role: making others the perpetrator and yourself the victim.

2. observe

It helps to start by simply observing how you yourself act – especially as a mediator; to form hypotheses about how you would act without the cognitive glasses of the drama triangle and how others would react if you did this or that. In this way, inner distance can be gained. This opens up flexible reaction options again – and the experience of feeling forced, pressurised and somehow sacrificed in the conflict dissolves.

Exit options from psychological games

What are then possible steps out of psychological gaming?

1. communicate perception

Communication of this perception in an ok-ok attitude and thus not in a role model of the drama triangle; but as a benevolent confronter who draws attention to contradictions fabricated by the communication partners. This opens up the opportunity for those involved to get out of the drama triangle and go to the „round table of responsibility“.

2. ask opening questions

Open questions that signal sincere interest and make clear the desire to clarify the situation and understand the person:

-

- What are we/you actually working on? What exactly are you currently working on?

- What do you want to achieve here? What do you want to achieve?

- What are we all about?"

3. demand decisions without pursuing them

If the personal responsibility situation has been clarified, appropriate decisions or activities can also be demanded. Accordingly, personal assumptions in this respect must be withdrawn ("I will no longer do this for you from now on...")

Attention: DO NOT DEMAND PERSECUTION ;-)

4. signalling care without rescuing.

Asking about needs and wishes is of course also helpful and permitted, but not on the condition that these needs or wishes are then also fulfilled. Players are usually unable to fulfil these things for the other fulfil.

5. register needs without making yourself helpless.

Psychological games often prevent real feelings from being expressed and important needs from being addressed and fulfilled; our child ego state is afraid of rejection and tempts us to play manipulative games. A game also ends when such dysfunctional behaviour is replaced by productive functional behaviour. But beware, there is no automatism here.

Establish an early warning system – Utilise experience

1. observe signal words

Note exaggerations, grandiosities, devaluations, e.g. "always", "never", "every time", but also "actually", "I'll give it a try...", "I'll take the time"...etc.

Also address ambiguities, question sympathetically what it is basically about if you suspect ambiguity. Or ignore them completely.

2. give and request appreciative feedback

Stroke with constructive feedback, take care of your stroke household, but don't suppress feelings of anger and other socially less adequate ways of addressing negative aspects.

3. no devaluations, no grandiosities, they provoke

4. do not think, feel or work for others – especially not for your clients, coachees or mediators

As a process consultant, you have enough other tasks and requirements to fulfil in order to do your job well. Having to deal with the tasks of others on top of this is usually overwhelming. This is all the more true if these tasks are highly personal, e.g. taking responsibility, making decisions, etc.

5. encourage and demand metacommunication early and preventively

Finally, it should be pointed out once again that not every communicative misunderstanding, madness or similar is already a psychological game. In conflict, it is more the rule that the parties involved experience misunderstandings and surprises on their direct path to clarity and mutual understanding. The part does not prove the existence of the whole. A game-like communication sequence is not yet proof that a psychological game is taking place.

What role does the concept of psychological games play in helping mediators organize mediation discussions to be free from psychological games?