Photo by Gianna Ciaramello on Unsplash

Strategic mediation.

A plea for an overdue change of perspective.

Part 2: Mediation and capitalism

So far, mediation has only emphasised its intellectual heritage in a one-sided way. It will only become effective when it fully recognises it: admittedly, humanism[1]freed man from his dependencies, increasing his power to almost immeasurable proportions: Not only the Religion and the Sciences experienced a revolution: man and his knowledge became the sole yardstick. Even the Economy revolutionised itself. Only conflict management did not keep up with the pace. Its revolution is still pending – or has yet to materialise.

Introduction

In terms of social history, the (Renaissance)Humanismwhich modern sciences and the CapitalismThese were interrelated phenomena that developed together and mutually in early modern Europe (from around 1600) and continue to exert their influence throughout the world today.

This one-sided view of its historical roots in (German-speaking) mediation has its origins in humanistic psychology, which developed at the beginning and middle of the 20th century with reference to existentialist philosophies. In the line of development of A. Maslow, C. Rogers, F. Perls and E. Berne, the human image and methodological reservoir of mediation unfolds[2]even if borrowings from other directions are increasingly being taken up[3]. Specifically, the focus is on research and pattern recognition of the human being as a free, autonomous, albeit social individual who is morally good at the outset.

While the liberating character is experienced positively, less attention is paid to the subjugating, power-accumulating character of humanistic development history, let alone integrated into the self-image of mediation, even though this would be helpful. In the discussions[4]This imprecision and uncertainty can be seen in the question of the influence of mediators. This second part of the article[5]gives space to the perspective of economic revolutionary capitalism.

Mediation requires not only a forward-looking product to support people and organisations, but also clarity about its own spiritual roots. In times of religious wars, humanism was by no means only aimed at pacifying people among themselves[6]and provided religious images of human beings for this purpose[7]which still have an impact today. Humanism also aimed at the material satisfaction of man, the domination of all life, including one's own. This materialism is by no means superficial, but has dazzling and seductive elements, fade-outs and devaluations that primarily affect non-human life and the environment. If we look at the things we conceive, invent, create and endure in the context of humanistic development, we must realise that we not only lose ourselves in them, but also find ourselves in them.[8]Simple causal chains do not help us to understand human development. This explicitly concerns the development of war and peace, conflict and consensus and is therefore interesting for mediation. It is true, for example, that peace makes it possible to do business together peacefully. It is equally true that doing business together secures, if not creates, peace. To name just one example. The question seems to arise again as to whether peace among people is the goal programme, the end of humanism, or rather the means to achieve something else: Accumulation of human power and domination of all other life in the world and beyond.

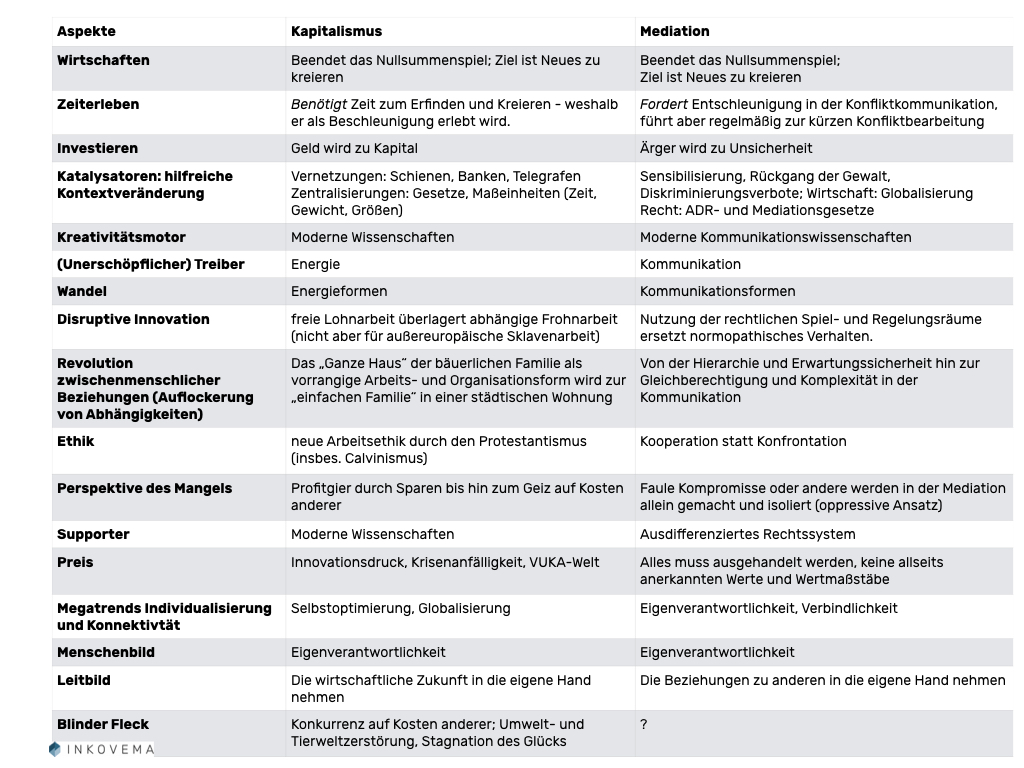

What does this mean for mediation, the mediation of social conflicts? In a humanistic context, mediation must be aware of these trace elements of its own development history in order to be effective. These individual aspects are outlined below or - for reasons of space - listed in tabular form.

1. when flowers (do their mischief)

It seems an irony of history that mediation wanted to enlarge the cake, but rejected the capitalist legacy outright. Today, the propagated opportunities for growth in conflict are understood in idealistic, emotional and relationship-orientated terms[9]but only very rarely explicitly in material terms. Instead of making the cake bigger for everyone, it is enough to grow emotionally and interpersonally. This one-sidedness has its counterpart in the overemphasis on the mediator's mediative stance[10]. As a kind of "inner existence", it is a typical expression of the humanistic construction of the world and leads to the fact that it is good all round, hardly open to criticism, but in the context of organised mediation leads to a discourse on attitudes; at worst to a dictatorship of attitudes to which the individual is defencelessly exposed. Attitude remains a seductive concept. For the individual, it is tangible, real and a yardstick for decisions, but in the group it is a pushing and oppressive concept, binding and oppressive at the same time. Its social pressure creates conformity, not originality. This may not justify criticism, but it does suggest a group dynamic.

From this flowering of mediation, it is important to get to the "roots of mediation"[11]to penetrate. They are more influential for the further development of mediation anyway. However, just as mediators can confirm that people lose sight of the essentials in conflict and usually react too violently to what is bad (about the other person), it is also worth slowing down here in order to recognise what mediation is and what is at work in its depths.

2. change of perspective: discovering the future

Capitalism is generally not considered (morally) good in humanist circles, whereas humans are, which is why the two are contradictory. It is capitalism that incites human greed, and therefore also inhuman behaviour; it awakens the worst human instincts and destroys interpersonal relationships. This view may have its logic, but it fails to recognise historical facts. Human greed is thousands of years older than capitalism – and humans, Homo sapiens, have not behaved better towards other human species or other animals without capitalism.[12]Even among their own kind, people without capitalism have communicated far more bloodthirstily than they have done business together. Globalisation bears eloquent witness to this. In fact, Homo Sapiens became friendlier, or at least more peaceful, when capitalism began to spread.[13]And it is no coincidence that this happened largely in the same place, in Europe. It was here that the conditions necessary for capitalism were created: First and foremost, the revolutionary view of the future.[14]

Until the 16th century, the future was something that belonged to God and was predetermined by him. Worrying about the future? For God's sake, no! Rather, it was appropriate to worry about God's favour. The future was not within man's sphere of influence. But in the decades of (Renaissance) humanism, early capitalism developed hand in hand with modern science[15]- and the future was discovered as a human endeavour. The future increasingly appeared to be something that could be shaped. People and societies realised that it was worth investing in it, no longer hoarding their money (like the church) or squandering it (like the nobility), but betting on the future, developing ideas today, inventing things, building devices that would yield profits in the future – but simply did not yet exist today. People began to make the future.

a. Win-win or those left behind are not always losers

And money became capital. Money was invested in the present for a better future. It enabled inventions, the creation of something new, which in turn would generate more money. Money as capital set the cycle of growth in motion – and the cake grew bigger for everyone. In 1500, the annual production per capita for the approximately 424 million people was 550 dollars. Today, the value for the more than 6 billion people on earth is 8800 dollars per capita. It was first and foremost a (second) revolution in agriculture that fed this number of people on earth, which was unthinkable a hundred years ago, but also a successful revolution in the capitalist economy as a whole. Of course, these developments cannot be attributed to capitalism alone, and modern science, the development of the state, the medical and hygienic revolutions and the overall decline in violence have all played their part. However, the original idea, formulated by Adam Smith, that the economic profit of the individual, reinvested in production, also benefits others and thus society as a whole, stands at the beginning of this European[16]characterised by global development.

b. Economy 3.0 – The end of a zero-sum game

After humans were increasingly less nomadic hunter-gatherers (economies 1.0) and became sedentary farmers during the Neolithic Revolution (approx. 12,000 years ago, economies 2.0)[17]for thousands of years, until around the 15th and 16th centuries, they were the Economy as a zero-sum game operated[18]What some had, others could not have. And those who were rich were rich at the expense of others. And those who were poor could borrow money, but such loans only alleviated hardship or, in the worst case, prevented death. These were by no means loans that were used to create something truly new, the profits of which then allowed the loan to be repaid. Accordingly, the interest on the loan had to be paid from the substance, not from the increase in value. In this world of scarcity, where economic activity was a zero-sum game, wealth must have been frowned upon.[19]It could only be anti-social, at the expense of others. It was not until the emergence of industrial capitalism that money became capital and the economy began to grow.[20]In conjunction with modern science, the future was tackled in order to free people from their dependencies and gain unspeakable power over life. Even if we do not yet know the end of this story, it is clear that the transformation from the stagnating economy 2.0 to the growth economy 3.0 was an astonishing cultural achievement by the people and organisations involved, who used their money as capital and led the economy to ever new increases in value.

In an economy that is growing, the nature of money, credit, interest and profits changes completely! Loans are no longer there to avert the most bitter hardship, but to make production more efficient and to invest in new products. Interest and profits are no longer paid from the substance, but from the growth of the economy. Capitalism has heralded an astonishing, one of the greatest changes of perspective in human history; it has turned the zero-sum game of the economy into a win-win situation for everyone.[21]

c. Reality-building expectations: The cake enlargement

How did this change in perspective come about? The fact that expectations have a reality-forming effect is not only a realisation that has been theoretically substantiated by psychology, but is also an experience of economic life. In 1938, the economist J.M. Keynes explicitly formulated this in his General Theory: "A monetary economy is,..., an economy in which changing views about the future are able to influence the amount of labour activity."[22]However, we humans do not move in a vacuum or in mental castles in the air. The changed view that the future could be shaped by people not only leads to an increase in the size of the cake: we also become more insecure. We can fail. If the future is up to us, failure becomes conceivable. This is the basis of a new insecurity and fear. Even historical enlightenment, which claims that the future was never in God's hands but depended on chance and other factors, does not lead to stabilisation. On the contrary, historical research shows that although it is able to enlighten us (intellectually), it also has an unsettling effect emotionally. The more we seem to know about the past, the more intensely we become aware of its multifaceted power.[23]Things can always turn out differently! That is not a reassuring slogan. Any linearity that provides stability dissolves.

3. confidence and optimism: we can do it. Let's just do it!

Uncertainty demands trust, concerns optimism. If everything is in flux, little remains fixed. Capitalists, if not blessed with trust in other people, are at heart the optimists of life. They rush into the present with wealth they don't have (credit, investments) because they believe they can repay their debts. And as far as they have money, they invest it, always at risk, instead of hiding it in a piggy bank under their pillow. Let others do such stupid things, everyone thinks. This optimism is not only contagious in everyday life, but also leads to measurable economic, health, emotional and social benefits.[24]

What are the consequences for conflict mediation in the 21st century? In an economically and socially globalised world whose wealth stems from capitalist economies, conflicts are increasingly recognised for what they are: Occasions to renegotiate the future together and to dare to take new risks, new commitments and obligations.

Understanding the future as a malleable reality, no longer seeing the handling of conflicts as a zero-sum game, but increasingly endeavouring to cultivate other expectations, perceiving the potential of a win-win situation and investing together with optimism and trust – is also at the heart of mediation. For this to succeed, it is worth remembering the intellectual-historical roots of early capitalism, which already implemented a corresponding programme in the field of joint economic activity. For this reason, the goal of increasing the size of the material cake should not be rashly sacrificed by claiming that it is about inner, emotional growth and that common peace is the only goal. No, peace is – just like in business - a means to enlarge the cake and conflict is often the reason to finally get something baked together.

Overview

Footnotes / References

[1]Harari, Y.N.: A Brief History of Mankind, original 2015; 5th edition 2015; p. 280 ff.; ders. Homo Deus. A History of Tomorrow, Munich 2017; Morris, I.: Wer regiert die Welt. Why civilisations rule or are ruled, Frankfurt am Main 2012, Roeck, B.: Der Morgen der Welt. History of the Renaissance, Munich 2017.

[2]See Weigel, S.: Konfliktmanagement in der öffentlichen Verwaltung, Berlin 2012, p. 104 ff and 226 ff; on mediation Duss-von Werdt, J.: Homo Mediator, 2015.

[3]See the contributions in: Kriegel-Schmidt, K.: Mediation as a branch of science. In the field of tension between specialist expertise and interdisciplinarity, Wiesbaden 2017.

[4]Heck, J.: Der beteiligte Unbeteiligte. How mediating third parties transform conflicts, in: ZfRSoz 2016, Vol. 36, p. 58 ff.; Barth, Mayr: Der Mediator als Übersetzer, in: Kriegel-Schmidt, Mediation als Wissenschaftszweig, op.cit.; p. 161 ff.

[5]Part 1 – The strategic mediation, in: SdM 70.

[6]Roeck op. cit.; MacCulloch, D.: The Reformation 1490-1700, p. 871 ff.

[7]Harari 2017, 94 ff. 324 ff,

[8]Trentmann, Frank: Herrschaft der Dinge, Die Geschichte des Konsums vom 15. Jahrhundert bis Heute, Munich 2017, p. .

[9]For example, transformative mediation, see Bush, R. A. B./Folger, J. P.: Konflikt - Mediation und Transformation. Weinheim: Wiley 2009

[10]See only Spektrum der Mediation, 18th edition, Haltung in der Mediation, 2005.

[11]Introductory Hehn, Entwicklung und Stand der Mediation, in: Handbuch Mediation, Munich 2016, § 2.

[12]Harari 2015, p. 14 ff.; Morris 2012, p. 50 ff.

[13]Pinker, St.: Violence. A new history of humanity, Frankfurt am Main 2013.

[14]Hölscher, L.: Die Entdeckung der Zukunft, Göttingen 2016; Morris 2012.

[15]Roeck op. cit. p. 1034 ff.; Harari 2012; p. 336 ff., 374ff., 408 ff.

[16]Kocka, J.: History of Capitalism, Munich 2014, p. 46.

[17]Reichholf, J.: Why we humans became sedentary, Munich 2010.

[19]Hermann, U.: The victory of capital. How wealth came into the world. Die Geschichte von Wachstum, Geld und Krisen, Munich 2015, p. 129; On credit and interest since the 15th century, Trentmann, Herrschaft der Dinge, p. 543 ff.

[20]Hermann op. cit. p. 109 ff., 129; Kocka op. cit. p. 46;

[21]Cf. Hermann op. cit. p. 129, Harari 2012, ibid. 2017; Morris 2012, p. 473 ff.

[22]Keynes, J.M., General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, original New York 1936, 2002; Herrmann, op. cit.

[24]Worth reading on optimism Kahneman, Schnelles Denken, langsames Denken, Munich 2011, p. 316.

Leave A Comment