The creativity dispositive.

Creativity as a desire, aspiration and constraint in today's living and working environment.

From the margins of society to the centre

Cultural sociological insights and concepts according to Andreas Reckwitz

I. Introduction

Everything has to be new and everyone has to be creative. It is no longer just the artist who is creative and creativity is no longer something rare, special, innate that cannot be learnt, but a potential that people all carry within them – and actually something like the reason and meaning of life. Consequently, it is not only the personal, but also the personality that is created and what is created in the environment can always be an expression of this personality.

In essence, this is what the Berlin sociologist Andreas Reckwitz calls the creativity dispositive, emphasised in social and cultural history and thus essential lines of development in individual and social life. of the past 250 years and in this way makes it comprehensible.

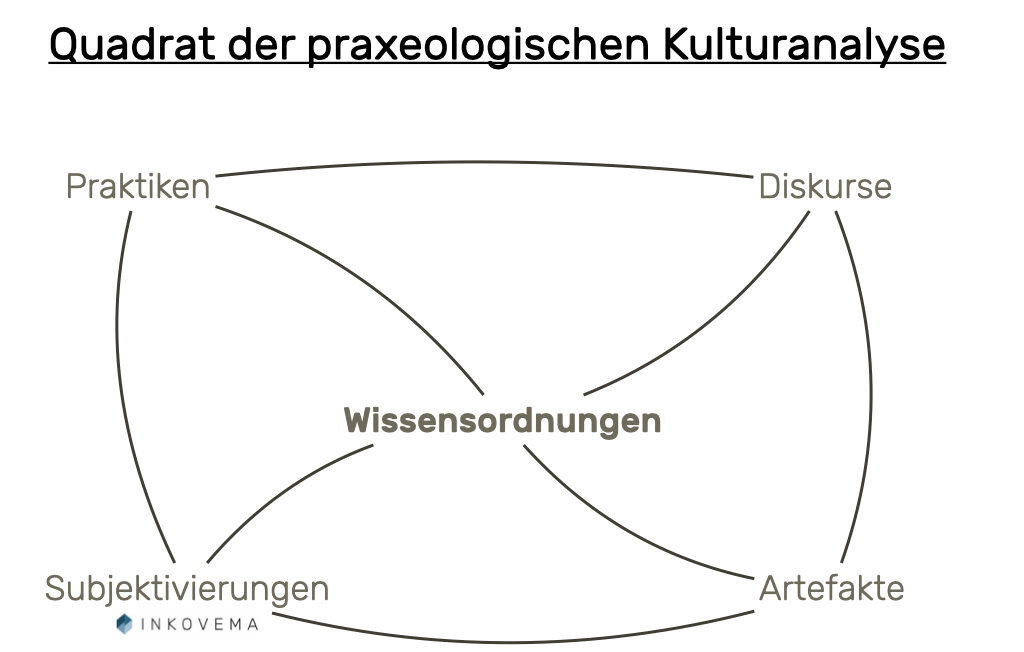

In order to shed light on this perspective, it is first necessary to clarify what a dispositive is. We then return to the concept of creativity. By way of introduction, it can already be said here that a dispositif is a social network of socially dispersed practices, discourses, artefacts and modes of subjectivation which, while not necessarily completely homogeneous, are nevertheless held together and coordinated by an order of knowledge. The dispositive, as Reckwitz interprets it with regard to Focault, who once introduced this term to sociology, is thus directly linked to the praxeological square of cultural diagnosis (see IE 2021-04).

II. What is a dispositive not

It is worth shedding some more light on the sociological context and drawing on other concepts that are not a dispositive:

1. a dispositive is no institution in the sense of classical or new institutional theory. This is because dispositives are about more than systems of order and rules that have been conceptualised as social institutions and that shape, form and influence the social behaviour and actions of individuals, groups and societies. In this respect, institutional theory clarifies a section of social behaviour, primarily with the intention of explaining expected actions.

2. dispositives are also No (differentiated, self-contained) functional systems in the sense of difference theories. For their part, these functional systems consist only of communications, while dispositives also include artefacts, modes of subjectivation and practices and not only what is understood as communication. Dispositions dispose and coordinate their specific cultural and affirmative logic and effect transversally to the specific functional systems of modern, functionally differentiated society – and in this way have an economic, cultural, pedagogical as well as legal etc. effect. In this respect, dispositives contribute to the de-differentiation of society. They have a homogenising effect in different discourses and communicative codes and practices.

3. dispositives are also More than a discourse. Discourses, for their part, define the languages and ways of thinking that are available at a given time. They determine how people talk about something and how they are not allowed to talk about something. This is at least roughly how discourse theories see it, which attempt to describe how such consequences of utterances arise.

But what are dispositives then?

III What is a dispositive

A dispositif in the sense of Michel Focault is an entity that, at a given historical point in time, primarily has the function of fulfilling an urgent requirement. It represents a specific historical and local response to a social problem. It consists of a "heterogeneous ensemble... comprising discourses, institutions, architectural facilities, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific Statements, philosophical, moral or philanthropic Theorems, in short: the said as well as the unsaid are included" (dispositives of power).

What Reckwitz particularly emphasises (in contrast to Focault) is the social affectivitywhich is based on a social dispositive. If the "subject is invoked", an affective and emotional process has always arisen – and if the subject submits to the invocation, it is because it is affected, emotionally moved and in this respect "passionately arrested" (Reckwitz).

The dispositive thus becomes a dispositive not only because it exercises power, i.e. comes across as (over)powerful, but also because it is emotionalised and thus culturally significant. Participation in it becomes a fascination, an act of satisfaction and gratification that has a culturally valorising effect.

IV. The creativity dispositive

The creativity dispositive describes the social and cultural-historical process whereby people in modern society are increasingly creative and at the same time increasingly want to be. Its emergence also led to a specific social aestheticisation that became part of the dispositive. The dispositive thus describes an individual and societal orientation towards the creative, which is increasingly not only a desire, but also a desire to be creative. also became a compulsion at the same time.

While religion and politics were initially the classic areas that conveyed meaning and satisfaction, in the modernising society this function was also fulfilled by the aesthetic-creative, which intervened in many areas of society.

1. Historical lines of development

The historical development of the creativity dispositive can be divided into four phases.

- Over the course of the "long 19th century" (1789-1918), the Preparation phase: Creative activity was the core of the romantic Speciality culture, which the emphasised the original intrinsic complexity and the "Re-enchantment of the world", which was desecrated by the enlightened, rational natural sciences. Practices, discourses and artefacts emerged not only, but above all in art, which would later unfold the model of "creativity". The discourse on the "originality" of artists, the growth of a bourgeois public interested in art, including the bourgeois contempt for artistic life plans. But in the bourgeois discourse, artistic genius is first of all pathologised. The art market itself begins to crave more and more "novelty".

- This is followed by the Formation phaseUntil the 1960s, the creative was gaining strength in various corners of society and forming a dispositive. On the one hand, the Bohemian and the Avant-garde movements at the beginning of the 20th century. Here, the „artist“ as a subject is practically an anticipation of postmodern man: always and in everything creative, sometimes chaotic, in any case self-centred and to a certain extent asocial. The postmodern human being will build on this and (self) distinguish himself everywhere. Few things are more revealing than today's culture of self-profiling in social media, whether privately (FB) or professionally (Xing/LinkedIn)! Postmodern man presents himself and is hardly conceivable without an audience. On the other hand, the field of Arts and crafts movements that try out creative economic practices; then there is the late bourgeois corporate discourseincluding the Organisational and motivational discourse. In psychology, the pathological nature of artistic genius is broken down head-on and the creative is viewed from a positive perspective. These are the beginnings of Positive psychology. It grows with Gestalt psychology, intelligence research and the Self-growth movement into the social and educational sphere. The mass media begin to produce film and music stars who join the stars of art. In general, art intervenes in civic life. The artistic, the creative is no longer reserved for artists.

- In the third phase there is a crisis-like compression of the individual fields: The so-called Counter Cultures of the The 60s and 70s tie in with the counter-cultural designs on bourgeois life. Silicon Valley blossomed here for the first time – San Francisco as a place of longing. In general, the art of postmodernism shows the crisis-ridden compression just as clearly as the critical discourse in the Psychology of self-realisation (beginnings of transactional analysis). The advertising industry, design and fashion, but also the emerging individual tourism (globetrotters!) as a counter-movement to mass tourism begin their "work of self-realisation through self-creation".

- In the fourth phase Since the 1980s, the Creativity dispositive The creative industries are becoming the cultural drivers of society, producing global stars, etc.; creativity is becoming the guiding concept of psychology and political urban planning, which is giving rise to creative cities that are now the world's trendiest cities. In addition, these scattered but condensed fields are linked to the all-connecting network of new technologies (internet and computer industry).

2 Why? An explanatory approach

Why do the cultural counter-designs to bourgeois and (thoroughly) organised modernity (student, soldier, taxpayer) find such resonance? One important point has already been made: Classical modernity is so radically rationalised, completely plan- and progress-oriented. The scientifically progressive world of the industrialised state hardly offered any room for the sensual-affective, at best in consumption, in the church and with regard to the foreign peoples of the world.

Andreas Reckwitz paints a picture of cooling systems in early modernity, in which art, however, became a hot archipelago, the place of longing and compensation for the bourgeois class, in which sensuality and emotions were allowed, permitted and lived out, but also despised in a very popular way.

In an increasing "process of heating up", all other areas have been aestheticised and culturalised; politics, psychology and education as well as the economy, the media, the private sphere and urban planning have become affectively charged and can no longer exist today without emotions and an emphasis on feelings. Today, the aesthetic is therefore no longer limited to the arts or the countercultural sphere. Everywhere it is now increasingly about producing sensual-emotional events for their own sake. And it always has to be something new.

3. the innovative, the new

Reckwitz's thesis of aestheticisation, and specifically of the creativity dispositive, dates back to the end of the noughties – and even then he emphasised the new, the innovative aspect of the creativity dispositive. As the "new" does not exist objectively, but must – be determined in contrast to the old –, the question arises as to how this happens: Today more than ever in a creative interplay between competing producers and audiences. Just as the original artist could not have been cultivated without the audience, the new cannot be cultivated in modern society without the audience. This public society is cultivated in the media as well as in the economy or in art. For every social process, whether in the economy, in urban planning, in education or in politics, etc., it is no longer simply a matter of producing technically helpful new products, but above all of creating a new aesthetic and affective appeal that generates, binds and engages emotions.

V. Critical aspects

Critically and intuitively, the question arises: what is so good about the new? And the field of criticism of progress opens up. The decisive factor here is that society's focus on creativity is not something that only has positive things to say about it.

Because what is initially a win-win situation - the fact that people in our society want to be creative and should be creative or can't be any other way - is increasingly turning into a Compulsion. Creativity becomes a compulsion to perform, which always implies comparison or competition with others and can be psychologically stressful. It is then about "self-realisation", about originality: in the constant search for your own special self, you want to (re)create yourself (self-creation). This has become a social expectation. And this imperative relates not only to the profession, but to the person as a whole: the failure of the project of self-realisation thus becomes a total Failure of the whole person. The result is inadequacy disorders such as burnout and depression.

The strenuous nature of creativity is also evident elsewhere: At least if you don't apply this term to everything that people do without any contours. Creativity is also required in economic processes and the capitalist economy is a creativity machine that requires effort because it promises relief. Consumers who do not want to take the strenuous side of this creative process can pay dearly for the less arduous aspects. Consumption offers aesthetic stimuli and cultural experiences that may be psychologically and financially draining, but are far less strenuous than inventing the products that are being bought. But the astonished buyer is part of the creative world in which he lives because, as a buyer, he also provides feedback, incentivises new products and ultimately co-determines the new, the truly creative. And this is how what we experience everywhere every day today enters the world: Creativity is not only an educational, but since modern times also a An economic hopewhich sometimes destroys itself, but in doing so creates new incentives. Nowhere is this clearer than Pivoting of young entrepreneurs.

The creativity dispositive in the world of business and labour

Contrary to what Luc Boltanski and Ève Chiapello claim in "The New Spirit of Capitalism", Andreas Reckwitz does not see creativity and self-realisation as capitalism's new instruments of oppression. The demands for creativity and innovation are not children of capitalism! For Reckwitz, it is a reciprocal process in which capitalism has penetrated aesthetics: modern art proved itself early on to be the forward-looking market in which not only originality but was sold as an "attitude to life", which was later adopted first by advertising (car brands as an expression of character!) and then by the entire economy (bicycles as a political statement). And in this respect, it is also the case that the economy has been aestheticised.

The dispositive of creativity can be seen in the economisation of all areas of postmodern life. The interlocking of aestheticisation and economisation practically forms the core of the creativity dispositive. What has been called the motivation problem of organised modernity has largely been solved with the help of aestheticisation and self-realisation. The economisation of social and individual life promises aestheticisation and self-realisation effects.

VI Significance for counselling

If you want to understand postmodern organisations and organisational members, you have to consider the creativity dispositive. This becomes clear when we want to understand the motivational processes of the organisation and its (potential) members. Employer branding, war for talents, Generation X,Y,Z, New Work etc. – are all facets of discourses that appear in coaching and counselling.

However, the creativity dispositive is also decisive for mediators, if not even justifying: the fact that conflict is no longer merely a flaw in the organisation of organisations, but a starting point for new, creative solutions, is striking. The modern understanding of conflict is also an expression of the creativity dispositive, the fact that conflict is a creative confrontation with basically good intentions can hardly be understood as the result of social change without the creativity dispositive.

Leave A Comment