Structural change from a modern to a postmodern society

From the Doing Generality to the Doing Singularity

Cultural sociological insights and concepts according to Andreas Reckwitz

I. Introduction

Looking at society, Reckwitz recognises a fundamental change in social practices since the 1970s. What was previously the norm has since been in retreat, what was considered a fringe or counter-cultural phenomenon has since gained dominance. Countercultural movements, such as the 1960s so-called. Counter Cultures in the modern age have become a formative and present part of the Western world as perceived and perceivable through the media. This is the subject of the first draft of the institute.

Reckwitz abstracts this change and recognises an increasingly repressed Logic of the general and an increasingly striving for dominance Logic of the special, from Doing Generality (see II.) to a kind of Doing Singularity (see III.).

Reckwitz attributes this change since the 1970s in North America and Western Europe to three factors as driversas drivers of change that continue to have an impact today. These drivers are briefly presented below (see IV.) and concretised in the following three institute drafts.

II Modernity (19th-20th century, doing generality)

A process of formal rationalisation has long been recognised as characteristic of modernity in contrast to the early modern period. In all areas of society, initially primarily in the economy and the sciences, modernity is characterised by structural elements that can be described as

- Standardisation,

- Formalisation,

- Normalisation and

- Classification

could be described as. The path of the West was framed by normalisation and standardisation – and this industrially (=diligently) in all fields of social life. The measurement of the world had the consequence that it was made graspable and recognisable in forms, classes and norms (cf. Osterhammel, J.: The Transformation of the World, History of the 19th Century, Munich 2010; Roeck, B. : The morning of the world. History of the Renaissance, Munich 2020).

In terms of cultural history three stages in this process make up:

1. displacement of feudal and aristocratic society by bourgeois modernity

Initially, the bourgeois modernity, the feudal and aristocratic society: the early Industrialisation (Osterhammel: The Transformation of the World), the Scientificisation (Roeck: The Great European Conversation), globalised, capitalist production methods take up space, but also Democratisation and Legalisation (Codifications and standardisations of bourgeois society!).

2. displacement of bourgeois modernity by organised and industrial modernity

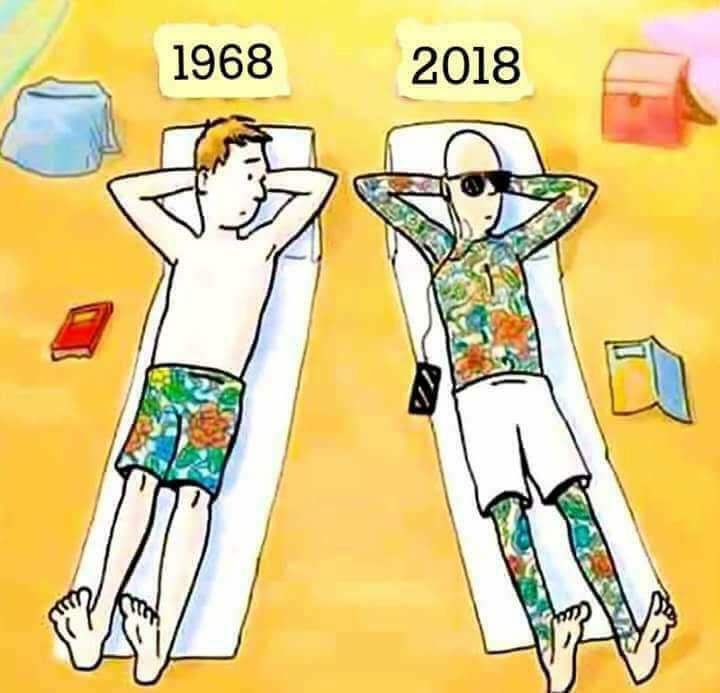

In the 20th century, the Organised and industrial modernity The modern era sets the social tone and leads modern society in its social logic of the general to its climax in the 1960s. Mass and popular culture has its presence here.

If you can't get a proper picture of this mass and popular culture of the time, Monsieur Hulot in „Tati's Marvellous Times“ (1968) will show you.

3. displacement of organised modernism by postmodernism or late modernism

In the Post- or late modernism the moment of culturalisation changes and takes on a new quality. The Counter Cultures take on the social character of society. Coming from the social periphery, namely art and culture, their social practices and the associated intentions for visibility, authenticity, autonomy and self-determination, unleashing and uniqueness become formative for society as a whole, initially in the university system and in education, then increasingly in counselling and in management discourse, later in living together within a family, but more and more clearly in the management of life itself. From standard of living to lifestyle.

III Postmodernism (from ca. 1970s, doing singularity)

In the post- or late modern era, the exception has become the rule – and dominates the process of further socialisation. Historically, the beginning can be located at the end of the 1970s in the USA and Western Europe. One Social logic of the particular (doing singularity) has been taking hold ever since.

This social logic of the particular manifests itself as the singularisation of social life into five units. It is important to note that singularisation is something different from the often feared or notorious individualisation. The five units of the logic of the particular are given their format as:

- Objects (artefacts, especially objects),

- Subjects,

- Spaces (places, cities, natural areas, etc.),

- Timings (events etc.) and

- Collectives.

These five units are activated and challenged by social practices, are consequences of co-operation, expressions of the creative and communicative. While social practices in modern society, especially in organised modernity, are based on a doing generality („That's how you do it – and not otherwise!“), e.g. through identical tools, idealised, i.e. standardised life courses (linear biography), through identical industrial sites, future-oriented, routinised time management and organised organisations, which then became frighteningly interchangeable, social practices in postmodern society are developing into a doing singularity and are subject to a social logic of the particular. Social practices are aimed at uniqueness, whereby the standardised has been relegated to the backstage of the social. They are self-evident, but not themselves an added value. The standard is no longer enough, the thing needs its own story and as much of it as possible (storytelling!).

Reckwitz identifies three drivers for these singularisation processes.

IV. Three drivers of singularisation

Ultimately, three social drivers support the process of change and peel the singularisation processes out of organised modernity into a postmodernity. These three drivers are

- the socio-cultural authenticity revolution,

- the post-industrial cultural capitalism revolution and

- the mathematical-technological digital revolution.

In social terms, their sources are admittedly scattered and can be traced back deep into bourgeois modernity (see Reckwitz, Das hybride Subjekt), but since the end of the 1970s they have been fuelling each other.

1. socio-cultural authenticity revolution

The socio-cultural Authenticity revolution is supported by the academic middle class, which initially made up only 5% of the population in the 1960s, but now accounts for over 30% in all western industrialised countries. Students are not an elitist fringe phenomenon, but – if you like – the „social norm“. But this purely quantitative aspect, which will be discussed in more detail elsewhere („New middle class“), is not decisive here, but rather the qualities that go with it.

Thanks to the explosion in education, this class has risen to the top and is able to achieve high cultural capital to show. The accompanying change in lifestyle, which seeks the "real", one's own and actual experience of life and moves away from the standard of living towards the Quality of life is now invoked from childhood onwards. The postmodern subject must live their best life if they do not want to feel the anxiety of having missed this opportunity.

It is the revolution of authenticity, which focuses the much-vaunted change in values as if in a burning mirror, and which is the change from Duty and acceptance values towards self-development values describes.

2. post-industrial cultural capitalism revolution

The economic revolution can be described as a process of culturalisation of the economic. While the economy of organised modernity was an organisation of organisation in the sense of a standardisation and formalisation of economic organisations, straight away with the organigram as iconography and exalted in capitalist Fordism and in Soviet state communism (e.g. in agriculture in collective farms).

However, since the 1970s and then especially since the 1990s, these organised organisations have been increasingly „ transformed“ into innovation-driven singularity machines that have to produce culturalised uniqueness (rarities+originals) in order to survive on the market – or perish.

In addition, there are signs of a change in the economy that will soon From a practical thing to a cultural asset could be labelled as a "brand". The practical, standardised object, whose price could be added together from production costs and profit, is increasingly about cultural goods, about brands whose price can be derived primarily from the cultural value for the customer. The market mechanisms for this have been adopted above all from the art market.

3. mathematical-technological digital revolution

It is the digitalisation of technologies, above all the media, with the help of which society is made visible and subjects, collectives, spatialities and temporalities are made visible. It is digitalisation that disrupts the routines of organised society, is a catastrophe of Gutenbergian proportions for it and granulates its elements – and singularises them in this way and in their visualisation.

It is this digital revolution, driven by portable, personalised computers, the internet and the AI-infused cloud, that provides everyone with the tools to plan, implement, observe, evaluate, reflect on and communicate about singularisation processes.

As already mentioned, these Three factors have interlocked since the 1970s and are the foundation of postmodernism: The academicised middle class finds professional activity primarily in the education and cultural economy (university and faculty boom, media, new media, etc.) and craves original, unique goods that meet their desire for authenticity, from yoga to yogi tea, from mindfulness seminars to alpaca jumpers, or even vicuña jumpers. What is striking is that luxury goods of the past have made their way to the centre of society – and for true luxury today, it has to be an island (with a little house).

I will address these three factors of societal transformation in the next draft of the institute.

Thank you for this compelling exploration of the shift from modern to postmodern society, and the role of design and structure in shaping our collective consciousness. Your thorough analysis highlights how evolving paradigms invite new ways of relating, creating, and holding space for diversity and emotional depth.

For readers interested in embodying transformation and connection beyond theory, there is the Ibiza Tantra Festival, Europe's first and only Tantra Festival. It offers immersive workshops, ritual ceremonies, breathwork, ecstatic dance, healing soundscapes, and intentional community gatherings-designed to support consciousness, healing, and holistic presence in lived experience.