Paradoxes of mediation

Voluntariness, confidentiality, self-determination, promotional…paradoxes of mediation that are important for mediators to understand their work

Table of contents

-

Starting points of the paradoxes that anticipate the end

-

The first paradox of mediation (McEwen/Milburn)

- The degree of voluntariness at the start of conflict mediation has no influence on the success of the mediation efforts.

-

The second paradox of mediation (Röhl)

-

Mediation appears to be more successful, more pacifying, not only legally but also socially, appears to be quicker and cheaper (than a court judgement, which is also said to expropriate the conflict) and better overall in social and individual terms, but remains unused.

-

-

The third paradox of mediation

- The second paradox of mediation also applies to mediators!

-

The EU mediation paradox

-

In 2008, the EU aimed for 50% of all EU civil disputes to be handled by mediation in 2018 and set out to realise this goal. In 2018, they achieved just under 1%.

-

-

The paradoxes of mediation in relation to confidentiality and trust

-

The confidentiality requirement of the neutral third party dictates social pressure. It is just as easy to be sued by the conflict partner as it is to sue them. But submitting to the mediation process together is extremely demanding - and not at all a matter of course. This is why mediation is a rarity in the sea of conflicts.

-

-

The paradoxes of the visibility of mediators

- Mediators intervene with autonomous individuals and advertise their neutrality

-

The mediation paradox and its resolution (Heck)

- The paradox that keeps dissolving

Starting points of the paradoxes that anticipate the end

Anyone looking at the mediation landscape in Germany – cannot help but be confronted with paradoxes.

So a few words about paradoxes, the phenomenon that itself seems paradoxical. Because Paradoxes by their very nature inspire thinking – and yet they often have a paralysing effect on those involved in conflicts and mediations. Those involved in conflict understandably demand freedom from contradiction and clarity, even if this means that disappointment is inevitable.

This article is also intended to stimulate reflection on the paradoxical phenomena of mediation. And by God (it's not possible today and not here!) – a few points of mediation require clarity and demand disappointment.

With the Concept of paradox – is borrowed from the ancient Greek „para“ = „against, against“ and „doxa“ = „opinion, view, belief“ – a contradiction, a dichotomy is taken up that cannot be resolved with conventional logic.

In the following, some phenomena of mediation and the mediation movement are taken up, which appear paradoxical from the perspective of mediation enthusiasts, although they seem quite understandable from another perspective.

As everywhere where paradoxes arise in an intellectual logic, it is important to recognise this paradox and work with it (in question mode!). Paradoxes are more suitable than almost anything else for changing the existing question and a suitable question in view that would escape without this paradox. Paradoxes can also be used to explain complex phenomena, at least in part. better to analyse or at least to differentiate the complex parts from the parts that have simply not yet been penetrated but can be penetrated in principle.

So – off we ’go – to the paradoxes of mediation, which we are already in the midst of.

„Let's spend more on grave care

than for further training?“

(unknown)

1. the first paradox of mediation (McEwen/Milburn):

The degree of voluntariness at the start of conflict mediation has no influence on the success of the mediation efforts.

As a mediator, you first have to let that melt in your mouth – and process it in your mind. This so-called first mediation paradox had already Craig A. McEwen and Thomas W. Milburn at the beginning of the 1990s in Negotiation Journal, 1993, 23-36, with her contribution Explaining a Paradox of Mediation formulated.

Especially in Germany, where the legislator has set the mediation principle of voluntariness extremely high in the course of the mediation movement, it seems downright grotesque that the degree of voluntariness to the mediation should not have any significant influence on the success of the mediation. Mind you „to “ mediation, not „in the“ or „during the“ Mediation!

But ultimately this is exactly the case: the degree of voluntariness has hardly any influence on the probability of success. The simple idea that more voluntariness leads to more self-commitment, more solution motivation leads to more solution identification and therefore to more sustainability is simply not true. Whether mediation fails or leads to success (agreement) is not significantly dependent on the extent to which the parties to the conflict were „pressurised“ into mediation at the outset. There is little reason to believe that this has changed over the past forty years.

Mediation efforts are not dependent on the initial degree of voluntariness – what does that mean?

But how should we understand this paradox? The first mediation paradox means that mediation efforts do not fail or succeed simply because the parties to the conflict were pushed into mediation or not. Pressure can come from the employer as well as from colleagues or relatives at home. The pressure to mediate, the compulsion or the obligation to enter into mediation only means that more mediations will (probably) take place, but not that the (failure) success rate will decrease or increase as a result of this pressure. It simply makes no significant difference, even if the personal explanations for the failure to reach an agreement suggest otherwise.

However, it is of course clear that nominally more mediations are started if the comrades are helped by compulsion and urge. But compulsion and urge have no general influence on the termination of mediations.

Mediators who only ever start to work when all parties involved confirm their voluntary – absolutely – at the beginning may therefore be giving away the experience of this paradox.

Excursus 1: It is still not clear whether mandatory participation in a mediation procedure has a significant impact on the success rate, what is involved in reaching successful agreements: In this context, the well-known legal sociologist Klaus F. Röhl has repeatedly referred to what he calls the Natural law of mediation According to this, around two thirds of all mediation procedures end in an agreement and one third do not. And this always applies if the parties have come to the negotiating table or have been brought to the table, regardless of how.

Excursus 2: The voluntary nature of mediation does not therefore have to be discarded immediately. There may be other reasons and addressees for this legislative intention. Even if the majority (2/3) of the conflict parties are satisfied at the end of mediation, even though they did not want mediation at the beginning, this does not directly speak in favour of a directive, paternalistic mediation policy.

Even if McEwen and Milburn thought that all you had to do was more or less force the disputants to the negotiating table so that they would come to an agreement voluntarily and thus force them to be happy. It can also be of value not to legislate this happiness. This is because rules and laws have an effect not only on the addressees who ignore them, but also on the observers who are addressed.

2. the second paradox of mediation (Röhl):

The second mediation paradox is familiar to all mediators looking around the mediation landscape today:

Mediation appears to be more successful, more pacifying, not only legally but also socially,

appears to be faster and cheaper (than the court judgement, which is also expropriatory) and

The potential to be more social and individually better overall remains unutilised.

This certainly applies to the present and the recent past of the last 30 years in Germany – measured against the hopes and wishes of all sides. Although hardly anyone says a negative word about mediation in public and despite all the good reputations and federal and European support, this remains soberly true at present: Mediation as a conflict management procedure has disappointed the hopes of both the judiciary and the mediation landscape.

And this is particularly devastating in view of the fact that in the past eighteen years (2005 – 2023), the state conflict resolution programme of the court system was shunned in a fabulous way that no one could ever have dreamed of in the last third of the 20th century. The waves of lawsuits in Germany ebbed away almost completely. The German civil courts were used less and less, even though the emergence of social conflicts had by no means diminished. Quite the opposite. (Now freshly published in May 2023: the Final report on the research project "Research into the causes of the decline in the number of applications to the civil courts", who is completing a three-year research project).

Nevertheless, mediation does not appear to have improved significantly in quantitative terms during this period across all fields of application.

Nevertheless, what the Legal sociologist Klaus F. Röhl as the second paradox of mediation:

- better (than other conflict management procedures, especially better than court proceedings)

- faster (than any other procedure, with the exception of the independent trial)

- Cheaper (than court, arbitration or similar proceedings)

- more successful (than other methods),

- but also – objectively and generalised – unused.

All those who could potentially be parties to the conflict are in favour of going to a mediator before they would involve the court – but hardly anyone does so in the case of their own conflicts.

3. paradox of mediation

The second mediation paradox also applies to mediators!

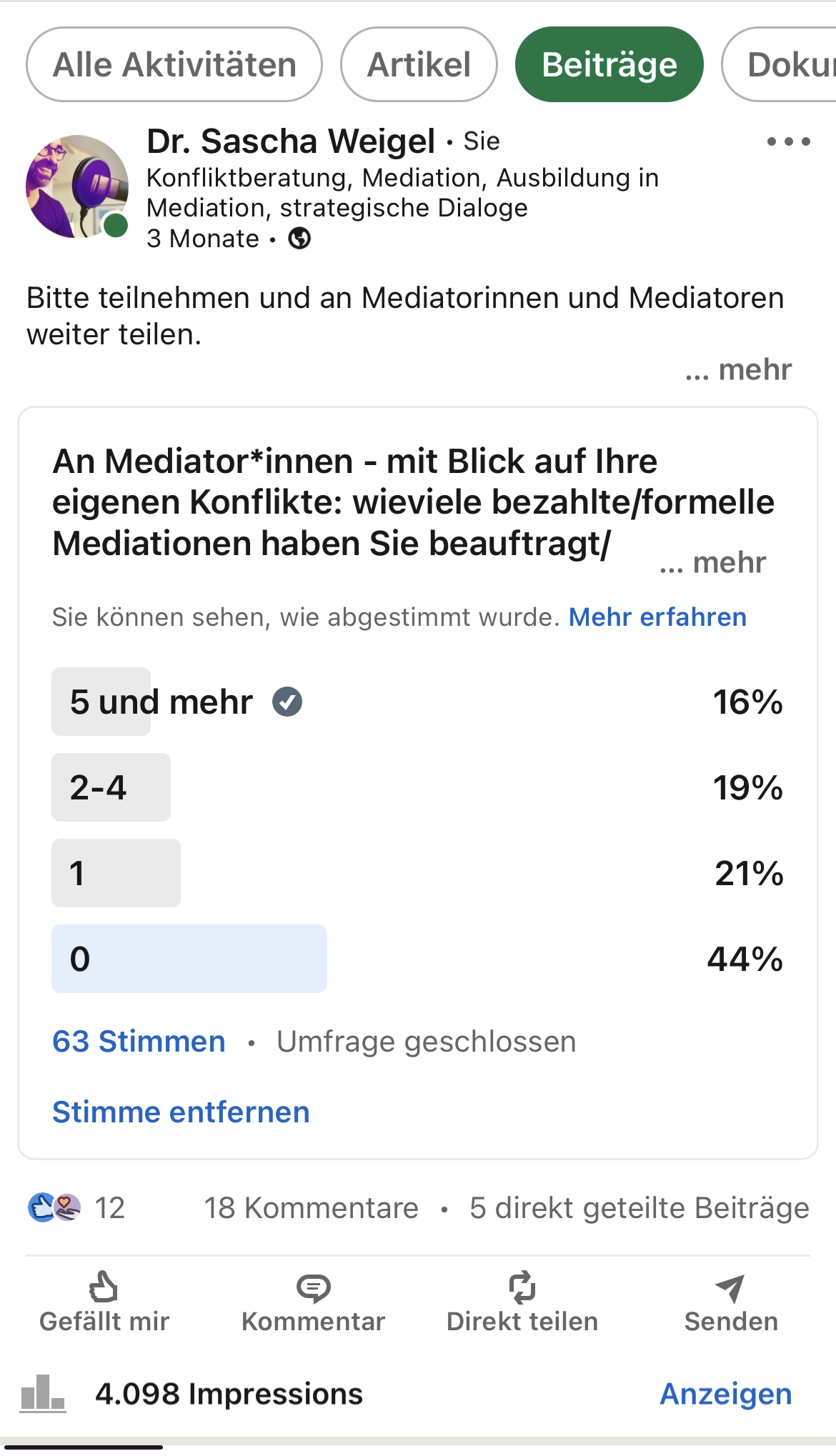

In a non-representative survey (the author of this blog post) on the professional network LinkedIn, mediators were asked to what extent they had already been involved as mediators in one of their conflict cases, i.e: How often have mediators commissioned mediation in their own matters? What was not asked (out of carelessness!) was whether and in how many cases mediation was suggested but then rejected by the other party or whether the respondent was asked but declined with thanks. However, the impact of this omission can hardly have been significant, because the comments on the survey did not draw attention to it in any way.

How were the Results?

- 44% of the responding voices had conducted 0 mediations.

- 21% have conducted 1 mediation,

- 19% have conducted 2-4 mediations

- 16% have conducted 5 or more mediations.

This means that almost half of the professionally trained people who are very familiar with the process have not yet been involved in mediation in their lives. That seems astonishing to say the least.

It is particularly paradoxical in light of the fact that one of the main reasons for the second mediation paradox was generally justified by the fact that the process is unknown and there is little experience with this product of experience. But this does not apply to mediators. They know about the process and the possibilities of conflict resolution.

In other words, almost half of the professionally trained people (mediators) who are very familiar with the process have not yet commissioned mediation in their – certainly no less conflict-ridden – lives.

In other words, almost half of the professionally trained people (mediators) who are very familiar with the process have not yet commissioned mediation in their – certainly no less conflict-ridden – lives.

It seems strange that the people who (probably) know mediation inside out, its effects and side effects - but hardly ever make use of this instrument and procedure in their own affairs. In any case, almost half of all mediators have no serious experience in the role of mediator! This is remarkable, downright strange. And seems paradoxical – at least in the case that mediators still have enough conflicts themselves. But why should the potential for conflict be reduced if you have completed mediation training? After all, the main thing taught there is that conflicts are normal and part of every life, right? So that should hardly be the reason why conflicts have disappeared for mediators. Rather, one could see the generally reported consequence of mediation training in the fact that the perception of one's own conflicts has been sensitised and the willingness to involve third parties as mediators can be found much earlier and more easily. In practice, however, this is not the case at all! And if you want to take the test, just go to a meeting of any mediation association…

And, please, don't get me wrong: I am not surprised that mediators – can also argue passionately with each other – cultivate their assumptions of entitlement and derive claims from both their rights and their concerns. I think that's normal. And I'm also not surprised that these professional mediators rarely have the idea of commissioning mediation themselves or encouraging their conflict partners to do so. They do this just as little (or often!) as the rest of the population. Only in very specific constellations in which many individual criteria are cumulatively fulfilled…

I am also of the opinion (and can confirm this for my own life) that conflicts are still part of life and that I have no less „ of them.

And I don't want to discourage mediation by pointing out the third paradox of mediation. There is nothing wrong with mediation! What I think is wrong and under-complex is the idea or claim that mediation should or could be used for the majority of conflicts and that it should always be given preference over court, as it were, because going to court is a kind of defeat for proper, sensible, social conflict management and the dance of death of escalating tragedy. It is at best a myth of mediation that going to court is the road to hell, but going to the mediator is the road to true, inner destiny.

I think mediation is a great invention; it is the supreme discipline of counselling and should always be used where a conflict system wants to be advised. This is what mediation was created for. And as with many counselling sessions, the reason is a certain inner distress, where little voluntariness is felt, but actually perceived. But with „an“ inner distress in a conflict system, it's a (special) thing.

Thanks to mediation, my experience of conflict has changed fundamentally once again, but by no means in just one direction. I have Five mediations in different fields, on different life issues and in different phases of life or be able to (co-)commission them.

However, I have never referred all my conflicts to mediation, nor did I ever intend to do so. Neither before, during nor after my training. Mediation was not the right tool for the majority of my conflicts – and joint counselling was out of the question. Contradictions sometimes also have to be fought outsometimes in the name of self-actualising personal development, sometimes to mature as a couple and sometimes to shed their couplehood.

4 The EU mediation paradox

In 2008, the EU aimed for 50% of all EU civil disputes to be handled by mediation in 2018 and set out to realise this goal. In 2018, they achieved just under 1%.

The so-called EU mediation paradox was labelled as such even by the EU. When it became clear in 2018, 10 years after the EU Mediation Directive 2008/52 came into force, that its objectives could simply and clearly not be achieved (read here).

In 2008, the target was that mediation would be used in half of the civil disputes (=50%) that would arise in the EU. What was achieved in 2018 was that mediation was scheduled in just 1% of civil disputes. And these figures were the result of all the financial and political support as well as the support efforts of the national judicial authorities of the EU countries. Directives, funding and public advocacy - they created 1%. 1% – which is much less than the targeted 50%.

Understandably, mediators are initially inclined to doubt the framework conditions of these facts, then to dispute the obvious conclusions and may still not abandon the hope that mediation „ is or at least should be the means of enlightened choice for a civil, participative and self-responsible society “. It simply continues to be asserted unwaveringly that the clear advantages of mediation are proven – and again and again in comparison to the judicial process, which would have to be compared to a butchery, in which the butcher's knife is either not sharp or has been missing for months and therefore nothing would progress. Amusing anecdotes and horror stories of court proceedings as background music, in which the parties to the conflict are either the driven and hoodwinked ones, i.e. the VICTIMS, or the stubborn, driven DRIVERS, who push the system to the limit and are ultimately not happy. There are plenty of these stories, especially from disappointed lawyers who know the business and have experienced unbearable cases time and time again. They want to be the SAVIOURS in order to – optionally – shed the victim or perpetrator role they once played. But unfortunately, there are not enough people willing to mediate.

And from this mediation perspective, it must at least be stated that the third, the so-called EU mediation paradox simply remains: It seems inexplicable why these people, who strive for personal responsibility, do not use this procedure in and for their conflicts. (Unless they are different from what mediators imagine them to be…but bear in mind that the third mediation paradox exists…)

As studies and research reports have shown, mediation has tended to develop in Italy alone. The background to this exception was the Italian opt-out model for the start of mediation proceedings. The opt-out model means that the first meeting of the parties in court already takes place within the framework of mediation. The parties involved can then decide not to continue with this procedure and to take legal action. For the remaining EU member states, the opt-in model applies: both parties to the dispute must agree in advance to start mediation proceedings. However, the parties to the conflict often decide not to do so – despite all the state advocacy, publicised advantages and legal disadvantages.

Despite promotion and massive support from politicians with laws, guidelines, finances and the like, but above all the mediatory certainty that it is simply the better, cheaper and more beneficial procedure: no significant demand from all the conflict parties, including all the mediators, who are also normal conflict parties in normal conflicts. Sometimes.

5 The confidentiality paradoxes of mediation

The confidentiality requirement of the neutral third party dictates social pressure. It is just as easy to be sued by the conflict partner as it is to sue them. But submitting to the mediation process together is extremely demanding – and not at all a matter of course. This is why mediation is a rarity in the sea of conflicts.

The confidentiality of the mediation process is considered by mediators to be a Essential principle of mediation. Essential in the sense that this confidentiality would make mediation possible. The more confidentiality, according to mediation thinking, the more and better mediation. At the same time, however, confidentiality is no constitutive principle! Mediation could also take place in public. Conflicting parties could mediate in the marketplace for everyone to hear and see. A first, small, hardly noteworthy paradox at the sight of the principle of confidentiality.

Let's stick to the basic assumptions of mediation: strict confidentiality opens up the parties to the conflict and enables them to meet each other honestly and without reservation, to explore and reveal their true interests. As if openness and honesty were static, monolithic phenomena that could be clearly and brightly illuminated in the clarity arena of mediation. This clarity not only leads out of conflict escalation, but also to the resolution of contradictions, human interests and needs are transformed into win-win situations where a joint solution can be found and communicated without power or violence. After all, we are all one humanity! Ultimately, according to the ignorant dictum of mediation, we all want the same thing and are connected to each other in our humanity: If this assumption is not authoritarian and dictatorial, then at least it is ignorant.

Human perception and memory are highly dynamic and contradictory, temporarily distorting, highly error-prone and, above all, not a mechanical and therefore repeatable process, but rather complex and chaotic. In (conflict) relationships, there is no objectively comprehensible clarity to be explored, but only constant negotiation processes in which the idea of clarity helps to avoid falling into bottomless despair.

Just as the mind is flat (Nick Chater „The Mind is flat“, Interview Link) and the self, a soul or (self-)consciousness is a mental illusion that enables and promises us identity, it must nevertheless be clear with Darwin that there can be no such thing (see Harari, Homo Deus, Munich 2017, p. 144 ff.). Here, as there, we are dealing with permanent processes of negotiation and actualisation that, like the spoken word, immediately evaporate, but could not be omitted.

But back to the paradox of trust.

Trust is one thing, confidentiality is another. While trust relates to the person, confidentiality relates to the communication space of the parties involved. A certain degree of trust is essential in mediation.

Trust itself is a paradoxical concept, as Luhmann has already made clear. Trust describes the expectation of certain events or their absence, which is risky from a sober point of view. Trust is – in Luhmann's words – the seager anticipation of events with factual uncertainty. Or to put it another way: those who (emotionally) trust must cognitively fade out. If you want to feel safe, you have to relegate uncertainties to the realm of the impalpable and invisible.

In the context of mediation, trust is at best a collateral damage of the process, which is made possible by the cognitive and emotional ignorance of the respective persons.

Now to the paradox of confidentiality:

Confidentiality concerns the communication framework of the parties to the conflict. The parties may assume that the other party will not disclose content from the proceedings to third parties without penalty/damage. This assumption of authorisation forms the starting point for achieving clarity and openness in and through mediation. Because that is what happens: The third party, and therefore outside the conflict, is approached for clarity and openness.

The key to the paradox is that although the degree of confidentiality is accepted in the name of openness and clarity, in practice this also means that mediation is conceptualised as a socially closed procedure. What is found out in mediation stays there. Or more honestly and openly: what is negotiated in mediation remains secret.

Its appeal also lies in the fact that, through mediation, conflict-resolving agreements remain confidential – and could at best be subject to scrutiny by the mediator. By declaring secrets to be socially accepted, mediation sometimes becomes a social truth grave. The Boston church scandal only came to public attention in the noughties, after many dozens of mediations, among other things, had led to the fact that nobody had seen and (because they were mediation talks!) could see the systematic nature and social extent of the crimes in the decades before.

The confidentiality of mediation probably creates a certain willingness on the part of those willing to reach an agreement to take the risk of openness, which is precisely what a relationship clarification on an equal footing requires; for others, this very confidentiality creates the possibility of sealing off content and facts and keeping them secret from authorities and affected third parties who, however, have a social interest in this information.

However, even parties to a conflict do not always have an absolute interest in absolute confidentiality, and this is fortunately recognised by the Mediation Act.

6 The paradoxes of the visibility of mediators

Mediators intervene with autonomous individuals and advertise their neutrality

A very practical paradox, if you will, is revealed in the a dichotomous entrepreneurship of mediators: How can one advertise an activity whose core performance could be described as social neutrality, restraint, even social ineffectiveness in the name of the conflict parties' own responsibility, but which should not be?

But no, mediators should and want to be effective, just not responsible for the content of the conflict and how it is conducted. The idea of the process emphasises that the parties to the conflict (should!) choose this path on their own responsibility, which they do not actually do in this procedural practice.

However, attitudes are gradually changing among mediators: They are revealing themselves, their needs and their services. Mediation is a service that needs to be advertised and explained because it is simply

- is counterintuitive,

- in need of explanation and

- unknown.

Re 1. – Mediation is counter-intuitive

No one simply comes up with the idea of mediation when they are in conflict. The primary realisation of Glasl's description of escalation is that in conflict, people intuitively seek to secure and increase power, influence and effectiveness, they seek to convince, to confirm, to forge coalitions or bonds with the powerful. Mediation, on the other hand, follows a social logic whose goal achievement, the mediation process, is based on highly idiosyncratic, strange and complex preconditions.

Re 2. – Mediation requires explanation

What distinguishes mediation from other conflict processes involving third parties is quickly and succinctly explained – and represents the whole deterrent force: Mediators have no decision-making power, bring no resolution and merely ensure that the parties to the conflict communicate directly with each other. But that is difficult enough.

If you don't want all that, you're in conflict. You want – much more! – to have nothing to do with the other person. The conflict should be resolved – and then you can do something again. And if the third party, who calls himself a mediator but is not yet involved in the conflict, also emphasises that he will not bring a solution, there is hardly any nerve left to understand what the third party actually wants to or can do. Mediators regularly disappoint the question about their services and fail to provide a comprehensible explanation when they answer, in contrast to the judge, that they do not provide a solution.

(BTW: of course they bring the solution! And the parties to the conflict implement this solution in mediation and see where it gets them. That's how it is with solutions that you have to make your own! It's the same with a court judgement).

Re 3. – Mediation is unknown

Just ask mediators about the three – most important service activities for the conflict parties – for which mediators (should) be paid.

7 The fundamental mediation paradox and its resolution (Heck):

The paradox that keeps dissolving

The sociologist Justus Heck presented his dissertation in 2020, which was published in 2022 under the title „The mediation paradox“, in which he explores mediation in disputes. Heck quite rightly locates the fundamental problem (fundamental paradox!) of mediation not only in the tension between mediation intervention and the self-determination of the parties, but also in the narrow understanding that conflict mediation only takes place in mediation.

Heck correctly assumes that the need for mediation in conflicts is enormous – and is by no means satisfied in regular mediation alone. Quite the opposite: mediation is the least effective. Conflict-provoked mediation needs are met much more intensively by the conflict system itself or in court. In both cases, a broad understanding of the term mediation can be used to identify activities that address and fulfil the identified need for mediation. In this interpretation, mediation is a procedural form of mediation. For this reason, the number of cases fell short of expectations, which are based on the assumption that mediation takes place exclusively in mediations.

This assumption does not only have to deal with the fact that demand is low, but also explains the enthusiasm and depth of hope on the part of the mediation scene. But that is another topic.

Leave A Comment