Why mediators ask –

but not why!

Questions as interventions in mediations and coaching sessions

Introduction

It doesn't take long in mediations and everyone knows: Mediators ask questions.

But why, what for, why – and how exactly?

In general, the following applies: In conversations, we can of course ask questions to obtain information, e.g. figures, data, facts, but also intentions and effects. But we can also – all together – questioningly scrutinise others, questioningly criticise, – loudly communicate – questioningly put ourselves in a good light and questionlessly overshadow others. We can always and everywhere – and not only in mediation or coaching – encourage with questions, praise with questions, but also intimidate with questions, downright belittle and ask derogatory questions; we can send information with questions, even ideas for solutions.

What we can't do, even if we believe that it must still be possible, is to simply ask, without context or intention.

That's hardly possible. We not only explore the world questioningly, but also reveal it – especially our own. And sometimes we lose ourselves and get stuck without question. By asking questions – and especially in mediation – we can protect the interviewee, but also those present and absent, and unfortunately also embarrass them.

Questions are a world in themselves – and – at least in mediations – the decisive instrument (in) world-creating communication.

An example for the beginning of what a question can do: "A Franciscan saw a Jesuit smoking while reading the breviary in a train compartment! He pointed out to him, somewhat enviously, that it was forbidden. „On the contrary“, he said, „I have the Holy Father's permission“. Astonished, the Franciscan later turned to the Vatican himself and received confirmation of the ban on smoking while reading the breviary. Furious, he confronted the Jesuit at the next opportunity. „Oh sorry“, said the Jesuit, „I forgot that you are a Franciscan and surely you asked if you are allowed to smoke while reading the breviary! “, „Yes.“ „You should have asked if you were allowed to read the breviary while smoking. “ (PS: I understand the example with regard to the question, but what it has to do with Jesuits and Franciscans has so far eluded me. Please feel free to leave any hints in the comments…)

Sense of questions: Effectiveness

1. the instrument

There are no good or bad questions per se. As instruments, their effectiveness depends on the intentions and contextual conditions. Questions are the central intervention in mediations and an artful craft of communication in general. They are an instrument of establishing contact, of communicative knocking. They are powerful because they demand decisions and lead to action. For example, it is not so easy to hold a conversation without asking any questions. Try it once – and you will realise how much you depend on questions to communicate. You will also notice quite quickly and unpleasantly if you are not asked any questions in conversations. (Questions are not only tests, they also make things easier.

Of course, a questioner learns something new from the answer. He receives data and generates information. However, mediation is less about this aspect. The decisive factor for mediators is rather the fact that the interviewee learns something new! Questions in mediation are the result of a selection process that is decided solely by the mediator. This justifies the Power of the person asking the question.

2. the effects relevant to mediation

- The questioning mediator leads the dialogue.

- The mediator asking questions "informs" the others about what is important to him.

- The mediator asking questions gains new knowledge and new insights about the parties involved - as do the listeners.

- The questioning mediator reveals his interest (in the matter and the other person!).

- The mediator asking the questions structures, sets her priorities, frames the topic and determines how to proceed with the current topic.

- The questioning mediator decides whether and how to give the participants time and space to develop.

Mediators divide in, to, from and sometimes forever. All of this shows that it is indeed the mediators who decide, like the parties to the conflict deal with their conflict. This procedural dominance is undisputed and yet it is only the wording chosen that shows what impact this has on the content.

Which question makes sense at which point in time and is therefore groundbreaking ultimately depends on the mediator's hypotheses. These hypotheses, whether conscious or unconscious, guide the clarification process. A key challenge here is that the mediator clarifies its hypotheses and assumptions, tests them and rejects them if necessary. This process takes place primarily in the mode of asking questions. Explicitly by asking questions of the conflict parties as well as implicitly of oneself.

3. questions are always Trojan horses too

- Questions always contain implicit, often unconscious assumptions on the part of the person asking the question;

- As a rule, questions also contain assumptions and insinuations about the interviewees and the content being questioned;

- It is not always possible to keep the assumptions as hypotheses mentally in abeyance and put them up for scrutiny. Some hypotheses sooner or later become the assumed truth.

- The questioner assumes that they have the right to ask, which is often a result of the role and function of their task.

- The questioner also assumes that the interviewee will answer and has an answer ready.

- Both also assume that this makes sense to accept and implement.

4. ways of experiencing and reacting to questions

- Questions can Helpful and beneficial are experienced. The reactions lead and are de facto the famous and longed-for "further step in the redemptive direction".

- Questions can also be Coercion and pressure are perceived. They have a constricting, confrontational effect, driving you into a corner.

- Questions can inviting, opening, widening, expanding possibilities are experienced. Such questioning invitations are answered with a view to one's own wishes and needs, which may only have been awakened by the question.

- However, questions can also embarrassing and exposing effect, downright obscene come along. The inquiring exposure of e.g. personality-intimate aspects through the question is replaced by the shameful answer to it, which cannot be refused by the interviewee.

- The idea that Socrates promoted independent cognition is unfortunately only one interpretation (of several). It cannot be ruled out that Socrates' powerful, penetrating, dumbing down, but focussed and pressing questioning and conversation may have undermined self-awareness and constrained the questioner's path of thought: The interviewee becomes a servant (Bodenheimer) who must follow the logic of Socrates‘ along with its implicatures and paradigms.

Power and dealing with power

Those who allow themselves to be questioned attribute power. Those who ask attribute power to themselves. Those who pay to be questioned show how much power they attribute to questioning. And those who allow themselves to be paid for asking show how much power they want to be granted, i.e. demand.

Counsellors, including mediators, are sought out precisely in order to have this questioning power, which selects the content, the focus, the person, the time and the sequence, attributed to them and to accept it. The pressing expectation that mediators should accept this power is justified. The task and role is to deal professionally with this assigned power, which can be withdrawn at any time. This needs to be learnt. And experience is necessary.

1. professional ways of transferring power back

Whoever is given such power and whoever accepts it, knowing full well that it can be taken away again at any time, would do well to clothe their communication in such a way that the conferred power cloaks the questioning exercise of power, as it were, but formally. The formal exercise of power implies the informal retransfer of power!

- Formulate questions as requests for answers and invitations to reflect: Requests can be rejected, invitations too. But they are both posed.

- Demands themselves lead to pressure, which causes resistance. And the Why question regularly leads to justification efforts and moods.

- Communicating the context is important: The context of a question is always the intention pursued and the ulterior motive, which can be consciously made transparent as a hypothesis. These intentions and ulterior motives should always be focussed on the task at hand.

- Communicating the reason for the question in the conversation – at this time, in this chosen form, all this helps to ensure that no resistance is built up.

- Explicitly include permission not to reply.

- Say thank you for the answer, because after the question is before the next question. But please don't send a bombardment of thank-yous.

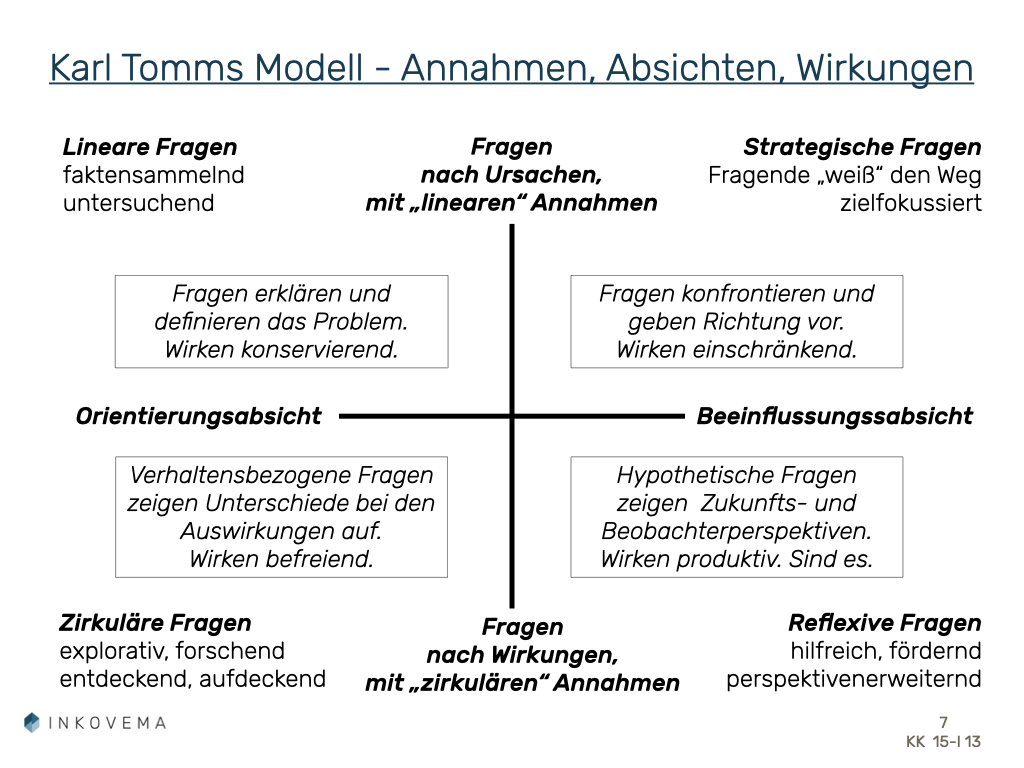

2. Tomm's map of questions and intentions

For this reason, a map of the question forms of the Systems theorist Karl Tommwhich also provides information about the intentions and presumed effects that are evoked.

Dear Sascha

Thank you for the exciting article!

In my coaching (parent coaching), I often use aspects of the hypnosystemic approach to convey alternative perspectives or ideas with questions, which can stimulate new food for thought in the other person. Often very effective.

Best regards

Mihaly

Thank you Mihaly for your response. Good luck and good luck with your work in parent coaching!