Practical diagnosis of an organisational culture with the culture diagnosis triangle according to Rolf Balling

A concept of transactional analysis for orientation in practical (counselling) work with and in organisations.

I. Introduction

1. idea of an organisational culture

With the concept of organisational culture, various disciplines – organisational psychology or organisational sociology, for example – attempt to capture what is considered to be an organisational culture. observe cross-personal patterns of interactions and decisions within and with organisations is. These patterns primarily concern the organisation's fundamental values and guiding principles.

The crucial point is that it is not simply a matter of „observing democratic rules of the game“ so that majority relationships are simply pattern justifications. Patterns can also consider rarely occurring phenomena, not simply what happens or is observed by the majority.

At first glance, the idea that organisations, like human individuals, develop a "personality" or their own „character“ or an overriding "atmosphere" that should extend beyond the sum of the individuals might seem daring. But in fact there is sufficient evidence that the effect of people in the "presence of an organisation" has a significant influence on their behaviour, thoughts and feelings. This is not surprising for a social being in a social system that is based on and works towards decisions (according to the functional systems theory concept of an organisation).

This is also the case in the Negotiation theory It has been found that people play the same game with the same rules more cooperatively when the background and purpose of the game is presented to them as a "cooperative game" than when they are told that it is a game of competition and competitive strategies. What this is ultimately due to and what the causes are (neurobiological, sociological, psychological, etc.) is ultimately irrelevant for our context and can be left aside here.

2. ideas on organisational culture

There are now various concepts and models for organisational culture. Concepts that explain what should and should not be included in order to determine the nature of an organisation's culture. And modelling that provides an indication of the methods that can be used to observe, measure and thus determine this culture.

This is how for example Ed Schein the organisational culture as a pattern of shared basic assumptions that the group or social system has learned in coping with external adaptation requirements and internal integration, which has proven itself and is therefore considered binding and is therefore passed on to members as a rational and emotionally correct approach to dealing with these problems. Appearance points out that organisational culture has a direct influence on key business figures, employee motivation and creativity. For him, organisational culture consists of three levels.

There are on the first level artefactsthat are directly and "objectively" observable.

Examples: Architecture, clothing, office design, logo, etc.; rituals, ceremonies, stories, legends, anecdotes, visible organisational structures and processes, organisational charts; workflows, documents, filing systems, social norms and rules

On the second level are the attitudes, values and norms which are indirectly expressed in the behaviour of the members of the organisation.

Examples: Strategies, prohibitions, goals, principles, philosophy (e.g. quality standards, appreciation of employees); latent orientation patterns that are only semi-conscious, values and attitudes can be at odds with basic assumptions;

On the third level are the basic assumptions which only exist implicitly and unconsciously.

Examples: about reality and truth; about time and space; about human nature; about human activity; about interpersonal relationships

Schein recommends various ways of exploring the organisational culture and shedding light on the individual layers:

Recommended methods: Questionnaires, Sity observations, Company tours, Individual meetings, Document analyses and in general Behavioural observations.

But this – is just a small digression that should help to broaden the basis of the basic assumptions for modelling our idea of organisational culture. This will help to make Balling's approach of a culture diagnosis triangle more understandable – also for yourself –.

II Balling's idea of organisational culture

Not scientific knowledge,

but communicative excitement the model should offer.

Balling's starting point for understanding the Organisational culture are above all (and entirely transaction-analytical) the communication patterns of the organisation members among themselves or in contact with non-members. It is not surprising that the transaction-analytical communication model is incorporated into his cultural diagnosis triangle. These transaction-analytical patterns also prove to be stable and surprisingly uniform in the organisational context. This is true even when individual members leave the organisation or are replaced.

It is one thing that these forms and contents of communication between the members of the organisation, as modelled by transactional analysis and thus (repeatedly) believed to be recognisable, are decisive. For Balling, however, they are also evident in the corresponding (organisational) buildings as well as in the company logo, lettering, advertising films, working methods and other rituals of the members. Here Balling presents his model just as broadly as Schein, even though, as a practising organisational consultant, he is not interested in a scientific model, but in practical help for the members of the organisation themselves. This is the crucial point of access to this model of organisational culture. Therefore the Methodological approach on the whole were not selected according to scientific criteria, but for the practical work of organisational workers. With the cultural diagnosis triangle model, Balling is not interested in measuring the cultural characteristics of the organisation and making them visible and understandable for third parties, the public, etc., but rather in preparing them for those involved and affected in order to enter into a constructive dialogue and critical discussion. The model is not intended to provide scientific knowledge, but rather communicative excitement.

Which topics are suitable for exploring the culture of the organisation?

- How are problems and crises defined and tackled?

- How is contact made with people, with customers, people who have shares, but also with individual employees?

- Which error culture is favoured in the organisation?

- Which risks seem to be okay, which are not?

- How are failures dealt with?

- How are former employees or bosses, and especially female bosses, spoken about? How is your farewell organised?

- What is conflict management like? How are conflicts recognised? What happens then?

- What are the company's "campfire stories", the founding myths, the visions?

- How do you deal with the official structures, the official channels and company cars, the specifications, the internal company regulations, etc.?

Balling believes that an organisational culture cannot be measured objectively, but that the observer himself is the diagnostic instrument. Quite a practitioner.

III Balling's cultural diagnosis triangle of an organisation

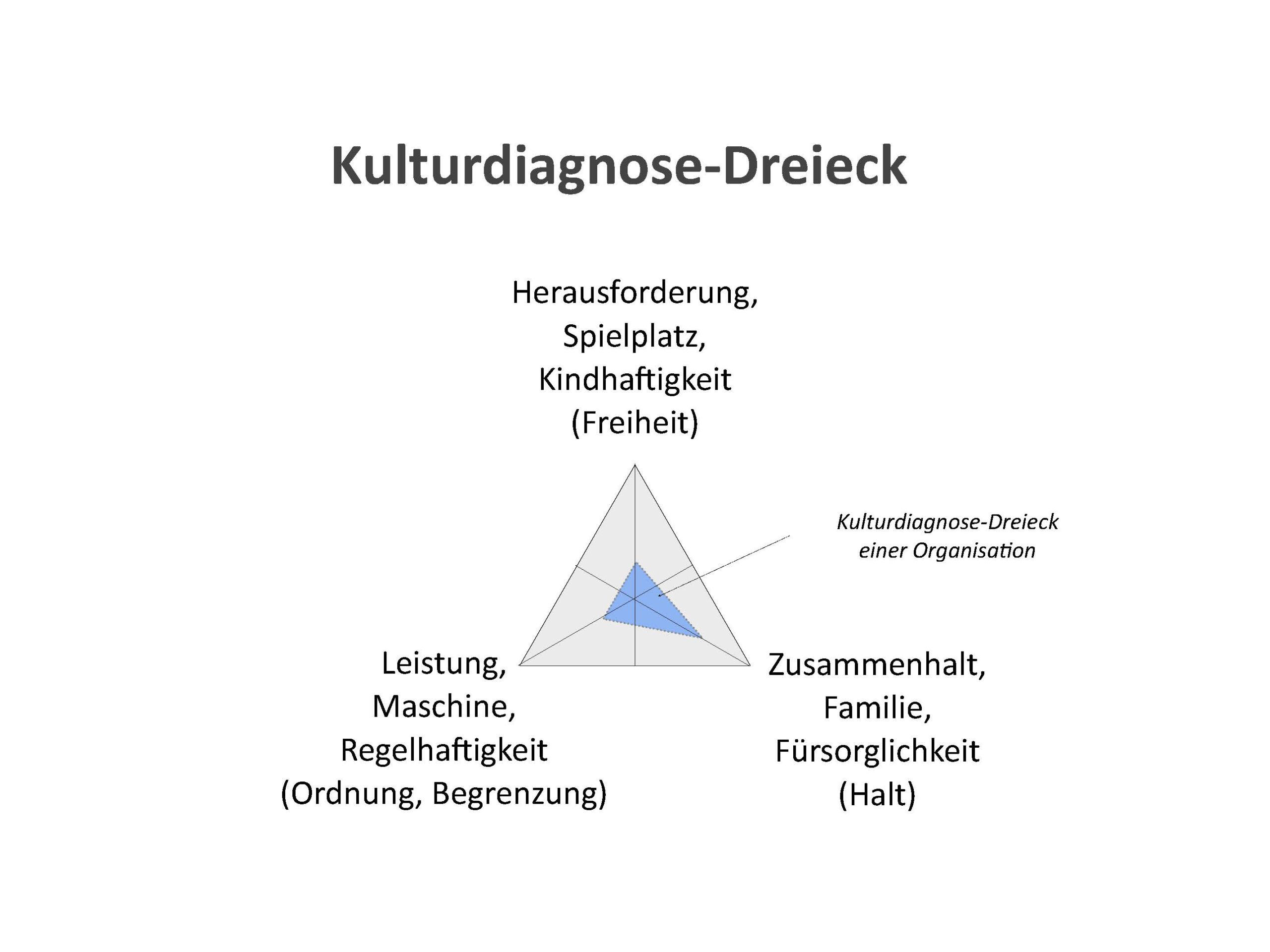

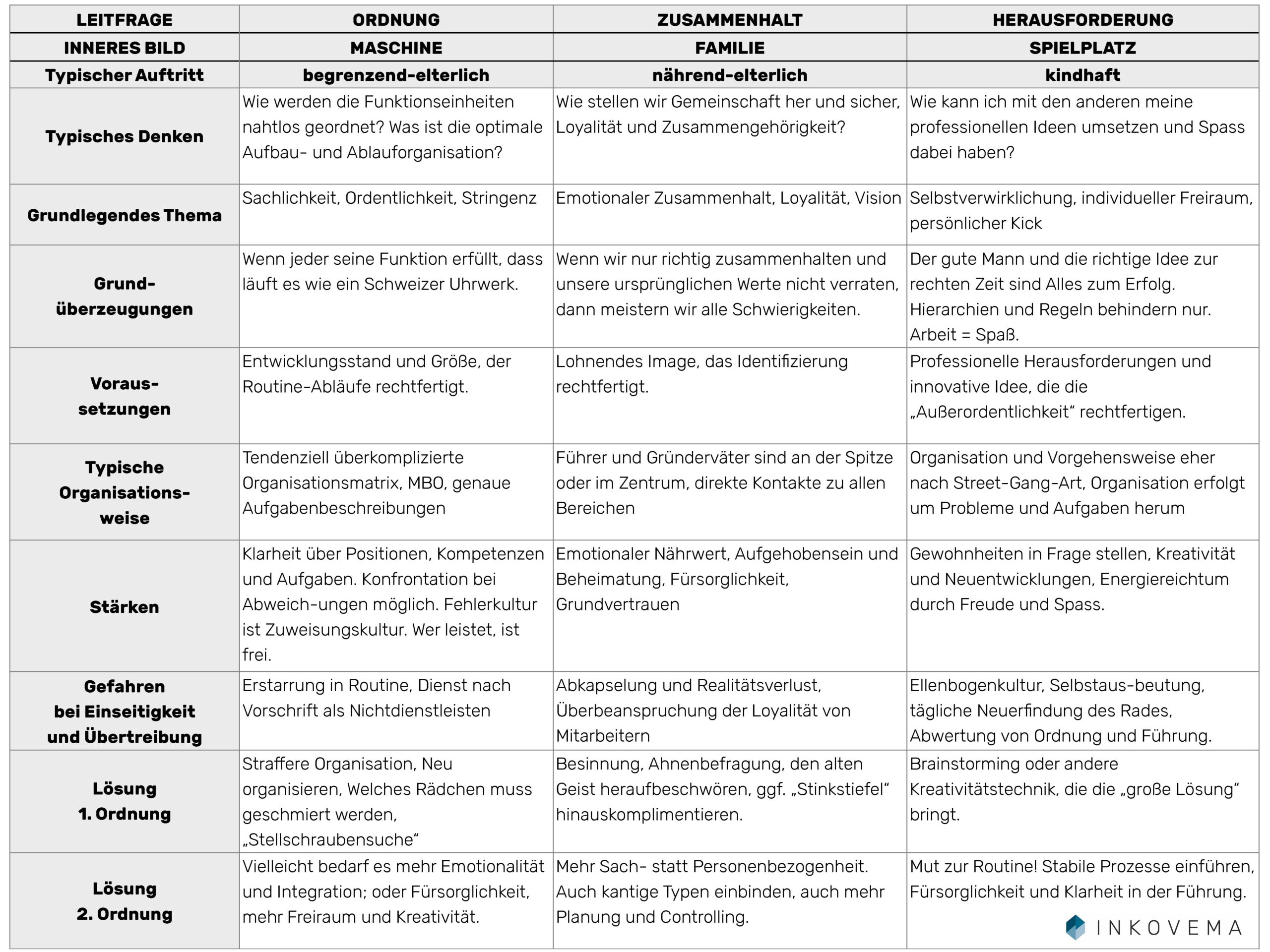

Balling states in his cultural diagnosis three key questionsto get to the bottom of the organisational culture?

To what extent does the organisation promote

1) the organisation or organisation of service provision?

2) the alignment or emotional orientation of the members?

3) the joy and creativity in the challenges that arise every day?

With these general lines of enquiry, which are organised in a very similar way to the Ed Schein can be determined, the inner (imaginary) images can be tapped, which in turn show their cultural traces.

1) The inner image of a machine based on order and regularityWhat is the quality of the design? How is the organisation structured and how does it run, which regularities prevail and to what extent? What can I rely on, whether pleasant or unpleasant?

2) The inner image of a family that is connected, whether it wants to be or not, and that keeps the connection in, out and through traditionWhat is the state of cohesion? What forms of appreciation exist, what rituals? What degree of caring exists between members and towards the organisation? How is over-caring dealt with, how is it explained, excused, tolerated, demanded or criticised? This relates above all to the question of the difference outside/inside – what differences are recognisable?

3) The inner image of a playground that promises joy, freedom and funHow exciting is it in the organisation? What scope is there for own projects? Is joy and fun allowed, what atmosphere is conveyed? How is joy and fun encouraged? To what extent is (children's) curiosity for professional ambition stimulated?

Balling recurs here to the three functional ego states as they Berne for communication and consistently continues the idea that organisations have their "own personality" by transferring not only the communication model, but also the transactional analysis personality model. In transactional analysis, too, it is sometimes assumed that personality consists of several „sub-personalities“ that are interrelated in a „Competition for effectiveness“ stand.

The typology of organisations should reinforce contrasts, as an organisation lives from its shades between the areas. No organisation can be assigned solely and exclusively to one type. This is why there are area-specific cultural characteristics: Manufacturing plants tend to have a "machine culture", training departments, internal training centres are often like large "playgrounds", while HR departments and works council committees seem to be responsible for "cohesion". It is precisely in this „observation“ of different cultural characteristics that Balling's model can also be recognised as a „postmodern cultural model“. This is because these „accompanying permissions“ and implicit assumptions or acceptances that organisations constitute such a diversity of cultural expressions and thus that different personalities also find a place in them as members is a postmodern trait of organisations, which is particularly evident in contrast to organisations of the so-called „organised modernity“ (Reckwitz). In this era of organisation, the main aim was to be organised as mechanically as possible, bureaucratically, in a fragmented way that could be represented in an organisational chart, in which members did not and should not strive for differences, but for uniformity, conformism and regularity. This was also the nature of the products that were manufactured, industrial at it’s best.

For Balling, this is by no means desirable – and his model not only takes these realities of the early 21st century into account, but also advocates them: teams and organisations should always have different elements of all three dimensions. It's the mix that makes’it. And it is the mixture that leads to the common organisational culture of an organisation that can no longer be organised or organised alone.

Dysfunctionalities are therefore also derived from one-sidedness and overemphasis, not from contamination and dilution. This also reveals the basic assumption of the model, which is based on systems theory. Problems, oh‘ what, problem definitions of organisational members must already take into account (and if necessary be stimulated with external consulting measures) that the answers to the key questions and derived solution approaches must not remain stuck on the same level of thought and order: Approaches to solving a problem from conceptualisation one are more likely to be derived from conceptualisations two and three.

IV. Consequences and advice for mediators and counsellors

- The model offers three drawers to categorise perceptible phenomena from the contact and order clarification phase onwards and to provide a more comprehensive diagnosis. It is okay that there are still uncertainties.

- The contrasts that arise in the classification into the three categories, which should not be resolved, help to enrich the counselling and mediation work in the following and to collect material for interventions.

- Despite all the differentiation within the parts of the organisation, the divisions, departments and collaborating professions, the overall classification also makes it possible to filter out a dominant cultural motif and to become aware of cross-divisional phenomena.

- On the one hand, avoid seeing every conflict that you deal with as a mediator in organisations as the result of cultural disputes, especially if there is a risk that the people involved could see themselves as being relieved of responsibility. On the other hand, the cultural diagnosis triangle also helps to relieve people of their urge to overburden themselves and to no longer see clear lines of conflict as personal problems. Here, the cultural diagnosis triangle helps to confront one-sidedness and overemphasis, i.e. to point out contradictions within the organisation and to support people in addressing these issues. (E.g. that structure and order can gradually be introduced into a start-up company that is no longer completely fresh, and that this does not immediately mean the end of the growth phase, freshness and creativity. With 30 employees, you are still a long way from being a bureaucratic corporate behemoth and you can calmly set up a binding and reliable process and put it in writing. And there can also be a second and a third, etc.).

- For Mediation in organisations The cultural diagnosis triangle is particularly useful when advising the internal client persons – because no conflict counsellor should too quickly adopt the client's solution idea that mediation is the right instrument. First of all, it is important to provide good advice and to understand the mandate to conduct mediation as the result of a prior counselling process. Mediation should not be seen as another playground, whereas it is more a matter of implementing management ideas – for which a mediator hardly seems suitable in mediation.

Leave A Comment