Practical case of mediation

Solution-free mediation as a success?

Complex mediation in the structures of a corporate group

Dr Sascha Weigel

Contents

The following account of complex conflict management is already several years old, the underlying case even older. Nevertheless, I have made decisive changes to several details and distorted the lines of development in order to prevent any backtracking and „late truth-finding“.

The presentation serves to make mediation work transparent and is intended to clarify which ideas can become significant in MEDIATION IN AND FOR ORGANISATIONS. It should help to give managers and mediators as well as mediation training candidates a picture of mediative work in and for organisations.

Even today, I am still indebted to every single person involved for their work and learning experience, although this can only be conveyed here to anonymous addressees

.

A. Opening credits

The following case is about mediation in a company in Germany, which was commissioned by the HR management in consultation with the works council and the department management. The reason for this was a letter from a black employee addressed to these three bodies, in which serious allegations and omissions were made against the team leader and her team assistant.

The starting point – and focus of the following description – were the conflict discussions in one of five teams in a department at the site. This team consisted of a total of nine people, seven ordinary members, one team leader and one team assistant. The mediation initially took place between the team leader and the black employee and then with the entire team. A specific conflict between the black employee and the team assistant, which was dealt with in an outsourced setting, led to the conclusion of conflict resolution in this department.

However, the organisation – as a consequence of the mediation discussions – placed the underlying topic on the training agenda of all departments.

B. Case description

In this case, my role as an external conflict counsellor and potential mediator began with a phone call from the works council chairman. He held out the prospect that I would be needed as a mediator in an escalated conflict and asked me whether I could imagine taking on this assignment. However, the matter was not easy, neither thematically nor personally. I already knew the works council chairman from other assignments in previous years. We had already been in close contact as part of the strategic orientation of the fifteen-member committee, so he told me straight away that he was not directly affected by the conflict and would probably not be involved in the mediation talks.

I was already interested after this phone call, as it seemed to be a complex and challenging conflict case that touched on intercultural aspects. I initially left open the question of whether it would be a suitable conflict case for mediation or whether other methods should be used.

I concluded the conversation with the request to first facilitate a four-way clarification meeting – with the head of department, the head of HR and the chair of the works council, i.e. the addressees of the letter from the black employee. This was because the mediation – or, at this point, more openly declared as conflict management – was by no means just a private dispute between the team members. Rather, fundamental values of the organisation and the interpersonal work process were at issue. Moreover, the conflict could not be resolved in the back rooms of the organisation and would remain secret. It was an organisational mediation that required the full support of top management in view of the issues involved (diversity, discrimination, racism).

1st meeting – Order clarification

Firstly, the head of department described how she saw the situation. The conflict in this team had been brewing for several months and centred primarily on the inadequate performance of the black employee. Her performance had indeed been categorised as inadequate using a performance recording tool, which had already been discussed more or less openly within the team. However, the team leader had only recently moved into this position, was very young and had now been caught completely on the wrong foot. She and the team had known for some time that there had already been arguments between the black employee and the team assistant. According to the head of department, this was not surprising as the team assistant had a huge influence on performance appraisals.

It was clear from the letter of complaint that the black employee had been suffering from the working situation with the team assistant for several weeks and had also informed the team leader of this. The accusation that she had been left alone by the team leader and the announcement that she no longer wanted to work alone in a room with the team assistant was therefore understandable.

In the course of the team leader's inaction, the black employee sought protection and advice from a social counselling centre specialising in gender and race issues. Here she found a person she could trust, with whom she discussed the situation and her intention to write an official letter of complaint. They assessed her situation as a case of bullying and discrimination and advised her to write a letter. The employee had been systematically marginalised and had therefore been asked by her line manager to approach others in order to end this isolation. Rumours were circulating about illnesses, gaps in knowledge and misinterpretations of various incidents. In addition, the supervisor had failed to fulfil her duties of protection and care. I already indicated at this point that this trusted person would very likely have to be involved in the event of mediation.

The HR manager and the works council chairman then declared their willingness to tackle the issue and commission mediation. This was also accompanied by a request to make recommendations for the further handling of the issue for the organisation's entire site. I ended the conversation with a declaration of intent to formulate a detailed offer in the next few days, setting out the effort involved and the procedure to be followed.

2. after the first meeting

After this first meeting and without having spoken to the direct parties to the conflict, the situation presented itself to me as follows.

a. Actual situation

The client system was an organisationally independent unit of an international group. This unit, spun off from the group at the beginning of the 2000s, provides services for the parent company. Its personnel growth surprised even the parent company. After just a few years, it employed more than four times as many staff as originally planned. The site had experienced an incredible pace of growth!

The site in Germany itself was staffed by people from countless nations, speaking several dozen different native languages. The official working languages were German and English. A works council existed in accordance with Section 9 sentence 1 of the Works Constitution Act.

The nine-person team in which the potential for conflict escalated consisted - as already mentioned - of the team leader, a male team assistant and seven employees (from four nations).

In addition to these actors, the trusted person of the black employee was also important. This was a volunteer social worker who, also a black woman, would play a decisive role in the success of the mediation. Without her, there would never have been any constructive and open discussions between the members of the organisation, as the black woman would not have been prepared to speak openly on her own and without support.

b. Considerations for the next steps

Two points in the process architecture were important in the further development process. On the one hand, it was important to ensure that the counselling system reflected the complexity of the client system: As a white, male, external mediator in a German corporate unit that consisted of over 70% women, but could not boast 10% female personnel on the management floors, mediation was unlikely to succeed in this constellation. In this respect, co-mediation was the obvious choice - female and, if possible, black.

On the other hand, it was important how mediation was given an organisational character in the specific case, i.e. how it could be carried out with the organisation in mind. This made it necessary for the organisation with its interests and concerns to always be "in the room". In this way, the conflict could be utilised so that the organisation could learn from and as a result of the conflict escalation and initiate sustainable changes. This necessity fits in with the topic of discrimination in organisations. There is a regular risk here that the blind spot of the organisation in mediation leads to the context-based conflict drivers being ignored and the individuals involved being isolated: Those who are structurally discriminated against are discriminated against precisely once again by the mediation that makes them alone. Mediation itself becomes a stabiliser of the organisational structure. Consequently, the mediator would also be part of this single-minded context that does not enable equalisation.

c. Co-mediation

As I was not a proven specialist in the field of "gender and race", I spoke out in favour of co-mediation with the client system. Here I was able to fall back on a suggestion from the person of trust, which had been submitted in the meantime. The willingness to mediate was also promised by the black woman if – in addition to her confidant – a second mediator, who had already been requested, would conduct the mediation together with me. That was a good match.

On the one hand, I made my advisory limits clear to the organisation in this matter and was thus able to meet any unrealistic expectations in a protective manner. Co-mediation was also an excellent way of reflecting the appropriate diversity in the obvious topics of dispute: While "one side" would (want to) talk about performance, key figures and "performance", "the other side" would want to talk about discriminatory structures and a problematic, racist working atmosphere. In order to lead both sides to a third level through mediation in such a case, which would be based on an appreciative ok.-ok. attitude, disappointment was necessary on the one hand (not being able to talk exclusively about one's own topic, "THE truth") and at the same time encouragement that what was initially divisive and contradictory could belong together after all. It was time to say goodbye to the idea that it was always the fault of who and what the real problem was.

It was ultimately agreed between myself and the client that we would work in a small group with the team leader and the black employee, possibly with the team assistant (4-5 sessions of 3 hours each), and then work with the entire team in team workshops on the fundamental issues and other "potential conflicts" in this context that had proved relevant for all those involved (4-5 sessions of 3 hours each). From the outset, in consultation with the head of department, we kept in mind that we would use the experience gained in this team to organise diversity workshops in the other department teams if it became clear that the issues were virulent across the department. To this end, we agreed regular feedback meetings with the client system.

Incidentally, the mediation talks took place on site in the conference rooms. Although I was not extremely satisfied with the conference rooms, I was able to understand the considerations of those involved. The tight work schedule made it seem like a luxury and a significant sign from the site management that an entire team was sometimes allowed to "take time out" of the working day for three hours. This was a novelty and was registered and categorised accordingly by everyone at the site: Something "meaningful" is happening here.

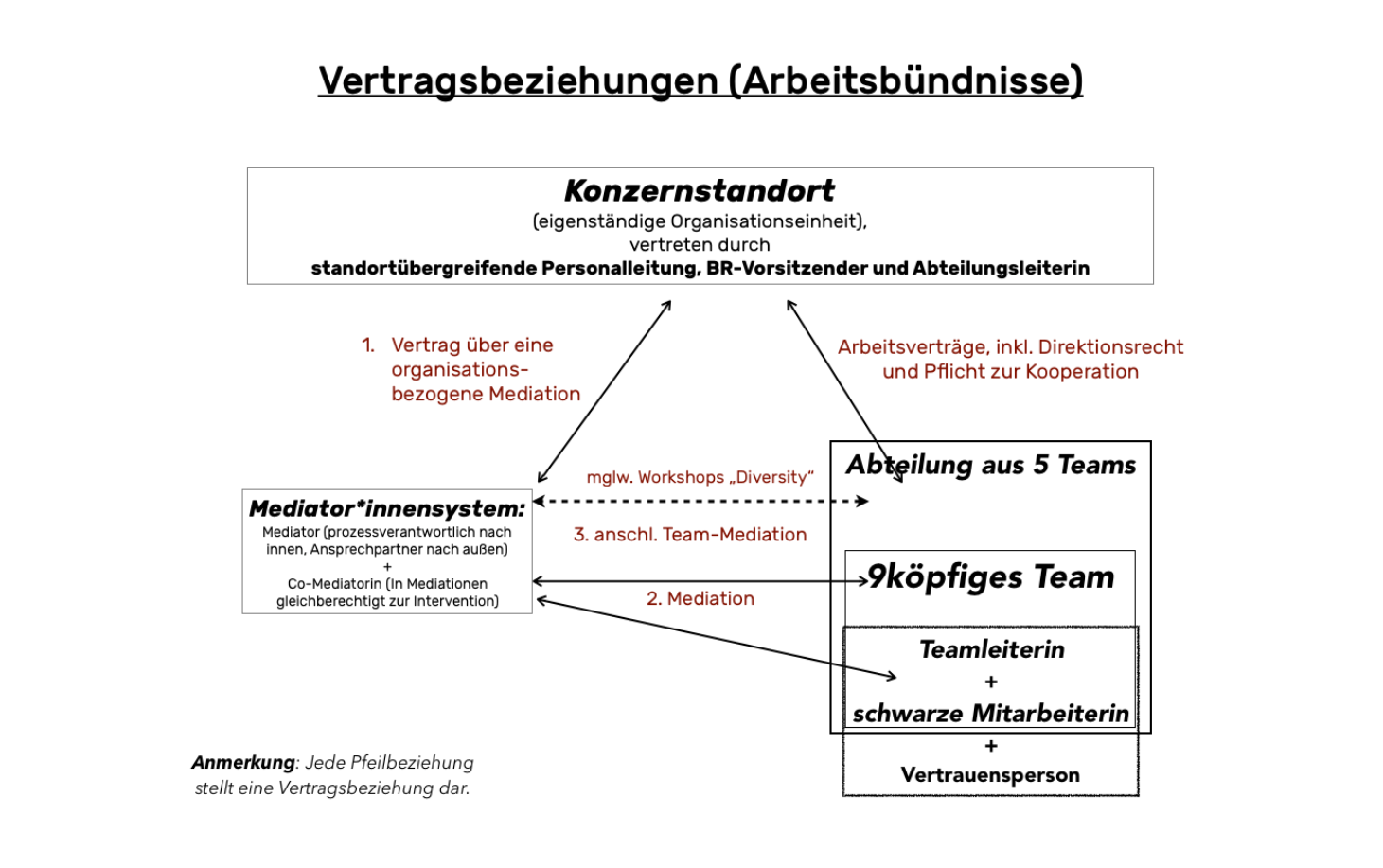

The overall working situation between the parties involved could be formulated graphically as follows:

d. Conflict issues and organisational culture

It was not surprising that discrimination was discussed in the mediation, which hardly anyone in the team was aware of. Team discussions centred solely on performance issues and the unwillingness of outsiders to adapt. This led to mutual discrimination and belittlement based on stereotypes. This is precisely the breeding ground for a poisonous, discriminatory atmosphere, whereby the organisational culture is likely to have had a formative effect: The proportion of women is over 70%, but they are significantly underrepresented in management positions (under 10%). The cohesion in an atmosphere of "friends" meant that no one was allowed to move away from the centre, neither upwards nor elsewhere: although the black female employee was not a so-called "high performer" (in the language of the organisation), she showed clearly demarcating traits of pride and aloofness towards her team colleagues, which only became understandable to them in the course of the mediation as protection and a way of dealing with the potential for conflict. She had previously been ostracised and socially punished for this. Team spirit arose exclusively through the question of who was "friends" with whom, not colleagues or otherwise work- and organisation-related.

For the It was therefore important for the overall organisation to establish the professional and organisational worlds in relation to the private and community worlds within the work organisation in order to avoid conflicts. In the Change portfolio from Balling hhe upcoming OD process is a leap in identity: professionalising interpersonal relationships would mean a transformative improvement in the quality of the organisational culture without having to fundamentally change structures and processes within the workflow. The envisaged attitude towards each other, that colleagues can also treat each other in a friendly, personal and approachable manner, even if they do not maintain a private friendship or "would not go on holiday with the other", would relax the working atmosphere and adjust the demands on each other to a realistic and beneficial level. A relevant learning moment on a personal level was therefore the distinction between collegiality and friendship, between the personal and the private, which the organisation itself had to cultivate and thus say goodbye to its "pioneer status".

3. extracts from the mediation discussions

a. Team leader – black employee

The first talks between the team leader and the black employee are about rebuilding trust: The East German socialised team leader literally fights to be seen as a supporter and promoter again. This is important to her and so it is easy for her to recognise that she has not understood and could not understand the perspective of the black woman. She therefore endeavours to provide intercultural leadership coaching, shows herself to be willing to learn and therefore strong in leadership. The black employee, who is a good 20 years older by the way, accepts this, but also makes it clear that there is a difference between them. "too much has already happened".

b. Voluntariness in the team

The first question that arises in the mediation discussions with the team is whether the participants are present voluntarily.

I make it clear at the beginning that I have a contractual relationship with the management to carry out this clarification and mediation process. The aim of this process is to discuss the different perspectives, interests and needs in the collaboration and to find a (new) basis for cooperation together.

The content of the contractual relationship is therefore to make the mediation skills available to the team as a unit of the organisation. I receive a certain fee for this. This is independent of success - linked to a single route: to clarify the conditions under which the team can work well again.

This now requires an (additional) working alliance with the team members. To this end, the management and I have given assurances of confidentiality as well as voluntary action on all sides, as can be seen from the individual employment contracts.

I make it clear to the team that this motivation is reflected in the respective employment contracts with the organisation: the employment contract as an expression of being able to work together in a team. Admittedly, this does not explicitly and literally stipulate that participation in mediation is mandatory. However, if the employer considers such a measure to be necessary in consultation with the responsible parties, participation at the beginning is at least covered by the right to issue instructions.

Well, being subject to a legal obligation is one thing, feeling the pressure to clarify is something else... The way the team members have been dealing with each other up to now - according to the participants' own statements - cannot continue, I interpret aloud at the beginning. One team member had approached the works council and superiors to initiate a clarification process.

The management trusts the team, I quote the client, that with the help of external support the team can resolve the unacceptable situation on its own. That is why it has not yet initiated any further measures. However, if the situation is not resolved, the site management will have to make a decision.

In this respect, mediation is voluntary because it is part of the employment contract, but it is not pressure-free. The conflict also exerts its pressurised dynamic here. The team members therefore have a conflict to resolve and this requires everyone's willingness; this is the work involved in mediation and therefore also takes place during paid working hours.

Ultimately, the feared negative consequences are no longer linked to mediation as a starting point, but to the conflicting team situation. Mediation is then accepted as an offer of a solution and not interpreted as an (involuntarily imposed) problem.

c. Team assistant – black employee

The following shows that a "flashpoint" of the conflict between the black employee and the team assistant still exists. In terms of the history of the conflict, this is one of the original sources that still requires acute treatment. After the mediation sessions, the team assistant writes several e-mails to all those involved, including the client system, in which he repeatedly explains his point of view and is outraged by the accusation of discrimination. As he explains in the discussions, he himself experienced as a child how his parents were humiliated and hurt as "immigrants who had moved here". He knows how bad discrimination is and therefore cannot be racist or discriminatory. These e-mails are clearly agitating and, towards the end, sometimes even "noisily" aggressive, as he believes it is about something else, namely the required performance of the team members.

We want to explore this stalemate situation between the two protagonists and their emotional communication about what it is actually about in the mediation. For this reason, in consultation with the co-mediator, I again form a small working group in the setting of a "classic" mediation, in which only the team assistant and the black employee and her confidant are present. The team assistant rejects the offer of her own confidant. However, we spend three hours working on just one question, which is of a preparatory nature but would be decisive for the progress of the mediation.

The team assistant is not prepared to speak to the black employee or to listen to her, as long as her confidant is present and authorised to say something. Incidentally, the team assistant is reservedly polite, albeit tense and still outraged by the accusation of discrimination. But everything hangs on this question for him: he tries to make it clear to the black employee in a downright agitating manner that she can trust him and that he is not racist, she just has to tell him what she thinks and wants. You can talk to him, he says, as he himself witnessed severe racist discrimination against his mother and himself as a child. He can't understand why he is dismissing the perspective and personal condition of the black employee.

We work here with perspective-changing interventions, have him repeat the woman's statement, summarise it again in his own words and make it clear that his own experience of discrimination neither protects him from acting in a discriminatory way himself, nor that a communication partner feels discriminated against because of his experience of the world. Even the framing that the perception of discrimination in labour relations is not the end and the condemnation, but the beginning of a deeper working and communication relationship, cannot be accepted. This path once again leads to the stalemate situation, which is a power play that the team assistant would feel discriminated against if the trusted person of the black employee remained present.

For the black employee, the presence of the confidant is a non-negotiable condition for being able to express herself in mediation. It gives her the balance to at least express herself in terms of content, if not to feel completely on an equal footing. The team assistant, on the other hand, does not want his own confidant and insists on only talking to the black employee and listening to her when her confidant is not present. For him, her presence remains an indication that he is being judged. It does not occur to him that this confidant is present for his dialogue partner and not against him.

There is no escape from this stalemate. Further offers are rejected and the decision is elevated to a question of identity, even though we make it clear that as mediators we cannot decide anything on this issue. Under no circumstances do we decide to fulfil this request unilaterally and thus ultimately perpetuate the established power structures. We do not ask the employee or the counsellor what they would think about continuing to work alone. We do not want to place mediation as a procedure in the context of the white man symbolically speaking determining the circumstances under which the black woman can act. We are taking control of the process here. That is why we interrupt any attempt to become substantive and move beyond this disagreement. Of course, we cannot dictate to the team assistant whether and how he should listen. The limit we set is that we would not become more substantive unless there is agreement on the setting and therefore the people present. The parties thus remain the self-determined actors in the process. We rule out a change of direction or a return to a more directive procedure (conciliation, evaluative mediation, etc.).

Without being able to go into detail here, it becomes clear in this three-hour individual session between the two that they do not want to and cannot continue working together as a team. It is not possible for them to re-establish a certain basis for their work and relationship, not even in the presence of support persons, mediators and process facilitators. This is the consensual result of this working group.

The potential for conflict, which had already been evident in escalating communication, evasive manoeuvres etc. throughout the previous weeks, can be shown clearly and acceptingly for both sides in this session. In the end, they agree that they cannot and do not want to work on their differences and similarities together. And they can "jointly accept" that the organisation will now determine the consequences.

4. consequences and agreements of the mediation

This was followed by feedback with the client system and clarification of the next steps.

There were two key points for the client system: Firstly, the developments in the team and the department, and secondly, the situation between the team assistant and the black employee.

With regard to the facts established between the team assistant and the black employee, the "personal centre of conflict", the client system drew the following conclusions in close contact with the two people: The HR manager, the head of department and the chairman of the works council came to the conclusion that both team members should be transferred from the team or from the entire department. This was by no means met with everyone's relief and approval, but it was tragic nonetheless:

- The black employee plucked up all her courage and reported her situation to the top of the organisation, initiated mediation and stood up to the superiority in the team - and was ultimately transferred anyway. This did not send a good signal to members of the organisation outside the team, of which the client system was aware and initiated appropriate communication measures.

- The team assistant was an important link within the team that had to be replaced. This caused enormous problems for the head of department, but she put up with them.

- There was a risk that individual team members would show solidarity with the team assistant and also want to leave the team or department. They interpreted the transfer as an organisational punishment and not as a personal consequence of their decision.

On the other hand, accepting these disadvantages was also a clear signal from the organisation: the explicitly laid down principles of diversity were taken seriously; it was by no means just a matter of key business figures that superseded the values of cooperation. The organisation was aware that it could only work sustainably if it fed the way in which good business figures were achieved into the overall accounts. For this reason, the underlying problems were also permanently addressed in all other departments and worked on together in workshops.

C. Conclusion

As a relatively new conflict resolution process, mediation is particularly interesting for the conflict case under discussion. The existing power structures and imbalances in an increasingly diverse (working) world pose a challenge to mediation. Its claim to promote individual autonomy and to use it as a benchmark has to incorporate social structures and historically evolved circumstances that ultimately (have to!) influence the actions of mediators. This case exemplifies this: mediation does not deal with conflicts without context, but within the framework of power structures and is at the same time a part of these structures itself.

An important concrete learning experience for the participants was to see that contact and constructive dialogue remained possible despite difficult and highly unpleasant topics of discussion. Even irreconcilable conflict issues can be negotiated and brought to a mutually acceptable solution on the basis of (agreed and impartially "monitored") cooperation and constructive communication.

The entire mediation process also led to comprehensive training measures in the other departments. Similar to an initial spark, the process also ensured that any negative side effects of diversity claims were addressed. In general, the – diversity claims formulated in glossy brochures were scrutinised for their realism and discussed seriously in practice by those involved. Overall, this was time-consuming and nerve-wracking and, although disillusioning in some cases, was largely strengthening and stabilising for those involved. Both were seen by the participants as coherent and beneficial. However, there was also dissatisfaction and incomprehension with the concrete results, as ultimately decided by the organisation. This should not be concealed here either.

What are the roles and challenges of co-mediation in handling conflicts related to issues of diversity, discrimination, and racism in international corporate environments?