The concept of psychological games in transactional analysis

Part 2: Procedure and forms of presentation

The drama triangle and play formulas according to Berne and Christoph-Lemke in transactional analysis

The psychological games are a Concept of transactional analysiswhich deals with communicative patterns of a manipulative nature. These psychological games are usually destructive in nature. Eric Berne, the founder of transactional analysis, was instrumental in developing this concept and published it in his – bestseller „Adult games“ („Games People Play“, 1964) was instrumental in the early success of transactional analysis as a School of Humanistic Psychology brought about.

In this second part of the small series of articles on psychological games it should be about the Procedure and display options of psychological games and thus about the Drama triangle by Stephen Karpman and the Game formulas from Eric Berne (Formula G) and the sensible and appropriate Extensions by Charlotte Christoph-Lemke.

A short series of articles on the psychological games of transactional analysis:

Graphical representations of psychological games.

Eric Berne once said in his legendary advertising orientation that concepts and ideas that cannot be represented graphically cannot be concepts of transactional analysis. Everything that is TA is also graphic, could be said in a nutshell, even if this oral tradition – as far as can be seen – has not been reflected in the literature on TA. Be that as it may…

The communicative dynamicswhich is conceptualised as destructive patterns in psychological games, is essentially represented (graphically) in two different ways in transactional analysis.

- The presentation (and categorisation of game types) is particularly common in what is known as the Drama triangle by Stephen B. Karpman. (See also the following articles in this short series).

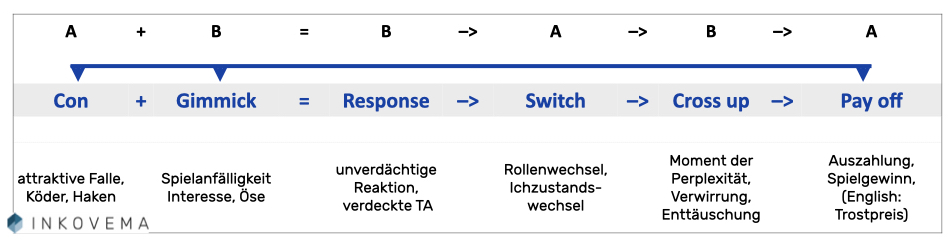

- The classic representation of Eric Berne itself, whose Game formulathe so-called Formula G, which characterised the beginnings of game design and was used in his bestseller „Adult Games“ from 1964. In the form of a mathematical equation, an attempt was made here to emphasise the inevitability and predictability of (unhindered) courses of play.

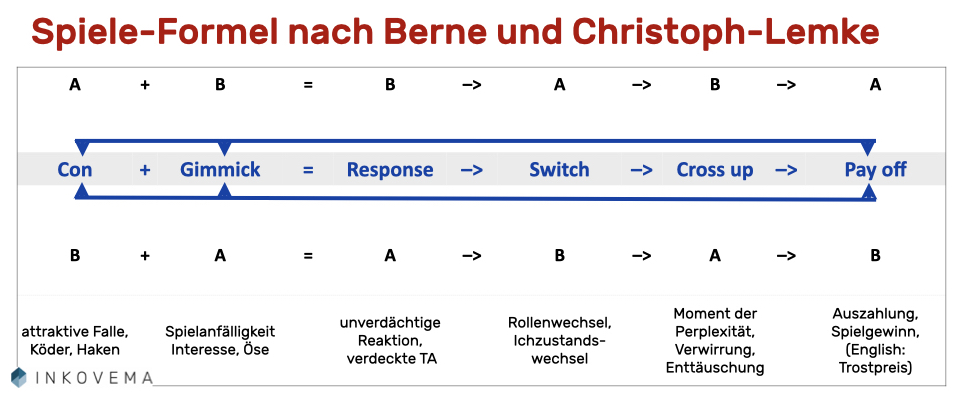

- It was later Charlotte Christoph-Lemkewhich the Game formula consistently. It is largely thanks to her that the reciprocal nature of the game roles and moves was incorporated into the formula. This is because one of the most important elements of manipulative games is the unconscious but collaborative element of the participants. If one person doesn't want to, two people can't play (psychological games). And this happened through a simple trick – Berne's game formula is presented as if in a mirror. And the way the game formula is used changes in practice. We will talk about this later.

If someone doesn't want to,

two cannot play (psychological games).

1 Karpman's drama triangle

The drama triangle as a concept for working in conflict counselling has already been discussed and presented in detail elsewhere in this blog. We refer to this article here.

2nd Bernes game formula

Eric Berne developed the concept of psychological games using a formula based on game theory, which caused a furore in the (economic) social sciences in the 1960s, in an attempt to depict a psychological game – in its course – in a mathematical way.

Excursus: This was very much the trend of the time. Perhaps you are also familiar with the Grid for visualising the prisoner's dilemma and the possibilities of the next move. Here, too, a mathematical, because game-theoretical, representation was used. In other words, this is how game theory was developed at this time. (Further links: Leidinger/Aman: Introduction to Game TheoryLecture notes on economic theory)

This Bernese formula looks at the communicative event from the perspective of one(!) participant. This implicitly reinforces the assumption that there is a player who is tempting others to „ play along with his“ game.

Berne's formula describes a player who plays and a „fellow player“ who is seduced, drawn in and manipulated.

This was the analytical strength of the game concept – and its conceptual weakness at the same time.

Definition and structuring of the characteristics of psychological games

Psychological games are

-

-

- Transaction chains,

- where A (game initiator) sets an attractive trap with an ambiguous stimulus,

- which arouses the (game) interest of B (potential player) and

- leads to an ambiguous reaction,

- so that a change of roles is encouraged,

- which leads to a moment of perplexity and

- leads to the payment of the (mutually unconsciously) desired winnings.

-

(1) "... transaction chains ..."

As games are chains of transactions, they are at least two people required for a communicative game to take place. As far as Berne and other transaction analysts believe that "one-sided games" are also possible (so-called "Head games", "solitaire games" or "fantasy games"), these are actually behaviours that do not have the character of a game, even if they lead to similar results (such as unpleasant feelings or bodily harm). They lack the transactional or communicative element. Three-sided and multi-sided games are, of course, possible. The transaction chains of a game can be continued indefinitely; their cursory, i.e. recurring character is decisive.

(2) "... attractive trap through ambiguous stimuli ..."

Games are initiated by the initiator A unconsciously choosing a "Attractive trap" (con) is established. Due to their covert transactions, games have an unconsciously ambiguous character that distinguishes them from operations and manoeuvres.

- Operations are also cursory. However, they do not contain any hidden messages. These are transactionally located on only one ego state level. In this respect, they are simple complementary transactions.

- Manoeuvre On the other hand, someone would initiate a game if they deliberately set a trap for someone else. Such a deliberate action is not a game because there is a lack of covert transactions in this respect. Players, however, act unconsciously or at least semi-consciously.

ExampleIf an employee repeatedly asks whether he is doing his work properly or always asks for praise and recognition, which he also receives and has often received, it is possibly, but not pathologising(!), merely a matter of operations, provided he is not communicating a hidden concern (Berne 2001, 41 f.).

(3) "... arouses the interest of a potential player ..."

The "attractive trap" snaps shut when the selected transaction partner and potential teammate "prone to play", i.e. it has a weakness in communication psychology in which the stimulus hooks and claims them. Bernes' perspective is clearly evident here, focussing on communication psychology aspects and taking little account of the social context and structural conditions. Or to put it another way: just as transactional analysis generally focuses on communication psychology, it ignores important influencing factors, but emphasises those aspects that have a significant impact. within the sphere of influence of the persons involved lie.

This communicative-psychological weakness of the person involved is called "gimmick" called. It often corresponds to a Script persuasion and is thus an expression of a Basic setting beyond "I'm okay, you're okay", which is why it is actually a psychosocial wound that still hurts in secret and could be resolved by restaging one's own play or co-play.

(4) "... leads to an ambiguous reaction ..."

B falls into the "attractive trap" transactionally, if and to the extent that he Interest in playing along (response) is signalled. This also happens through an ambiguous and unconscious message to A, so that the actual content is communicated and understood outside the conscious perception of both players.

This is also the transactional core element of psychological games:

Unconscious hidden complementary transactions.

Every player needs at least one other player, who however - and this is important - initiates their own game. People who prefer games that are complementary to their own game are therefore suitable as co-players. The action of B, which from the point of view of A is an interest in the game, is itself an invitation from the point of view of B - and vice versa. Game sequences are therefore complementary transaction chains of hidden transactions in which both players are unaware of certain levels. When it comes to the game Each initiator of their own game and player of another game.

This will also Basic assumption of decision-making ability and striving for autonomy The initiator of the game cannot force the other player to play, nor can he cause the other player to change roles in a linear-causal way. He can only invite ("seduce") him to play. However, each participant is and remains solely responsible for their actions even when playing (with another).

Example: According to Berne, the game recognised first is called "Why not - Yes, but ..." ("WANJA"). ("WANJA") and comes about when A describes a problem to others (B) in an unspoken way (e.g. heavy sighing, moaning, complaining, procrastinating, etc.) and asks B on a hidden psychological level to solve the problem by making clever suggestions. If B falls into the "attractive trap" by making suggestions without being asked ("Why don't you try ...?), A, as a shrewd WANJA player, will skilfully dismiss B's suggestions ("Yes, but that won't work because ...!"; "I've tried that too, but ..."). If B is a co-player in A's WANJA game, he is playing his own game as the main player: "I'm just trying to help you ..." ("IVEDIH"), for which he needed A as a player capable of making sacrifices. (More on this in part 5 of this series of articles)

(5) "... so that a change of role is encouraged ..."

B's ambiguous reaction encourages A to change roles. The Turnaround is introduced in the game sequence (switch). In addition to the unconsciousness of the players, this is the essential characteristic of a psychological game. A often alternates with the Game reel also the Ego state. These are the structural parent and child ego states. In the explanatory model of the "drama triangle", the original role of "persecutor/perpetrator or victim" is abandoned and changed to another. This new role correlates with the message that was previously communicated covertly.

(6) "... leads to a moment of perplexity ..."

The change of ego state and the associated change of role leads to a "Moment of perplexity" (crossup). This can be experienced as disappointment and is perceptible in physical and emotional sensations (winking, changes in sitting posture and breathing processes, blushing, dizzy spells, etc.). Since B is not only A's fellow player, but is also the initiator and main actor in his own game, A in turn, as B's fellow player, perceives the same in and for himself. This game sequence illustrates particularly well what applies overall: psychological games are circular communication processes that defy a pure causal description.

Psychological games are circular communication processes,

that defy a pure causal description.

(7) "... payment of the winnings sought ..."

At the moment of change and the realisation of one's own confusion, the disbursement of the unconsciously desired Game win on (payoff). These are the Confirmation of scripted feelings and thoughts about themselves, others and the world, so that the associated behaviour patterns are justified and stabilised. This game win is concretely defined right from the start, even if the player is unaware of it. The basis is the player's own Life scriptwhich is why the game win is often "surprising and yet often familiar".

Example: The "WANJA" player confirms his experience that nobody can help him and that he ultimately remains alone with his unsolvable problem or that the others are no wiser. Complementary "IVEDIH" players, for their part, confirm that nobody listens to them and that people are generally ungrateful.

3. the game formula according to Charlotte Christoph-Lemke

Charlotte Christoph-Lemke was a German transaction analyst who recently passed away in Munich in December 2019 at the age of 82.

In her contribution to the 11th Congress of the German Society for Transactional Analysis, she took up her practical observations and formulated accordingly in an essay in the congress reader that two players always act together and each plays their own psychological game. While Berne emphasised the game sequences from the point of view of one player and only marginally referred to a completing meeting of players, Christoph-Lemke placed this moment at the centre.

By "Formula G" (G-ame) with a feedback loop or mirrored representation, shows the changeability and complementarity of playing psychological games: For the conclusion is clear: there is never just one game being played, it is are at least two gameswhich are distributed among the players.

Everyone ultimately plays for themselves by talking to the others.

Attractive trap (Con) and susceptibility to play (Gimmick) are covert transactions that have a reciprocal, recurring character. The communicative contributions of participants A and B each exhibit both the character of an attractive trap for the other as well as their own susceptibility to gambling. The observable input sequence of the players thus shows the Starting point for two gamesthat are intertwined. Depending on the perspective (whose "attractive trap" would be declared as the cause), the roles are distributed according to perspective.

In this way, Christoph-Lemke takes account of the basic transaction-analytical assumption of Ability to make decisions and striving for autonomy The game initiator cannot force the other player to play, nor can he declare himself a victim of the other player's game initiative. The players invite each other to play and then each play their own favourite game. This is the SeductionCharacter of manipulative games.

In the following third article in the series, the concept of psychological games is placed in the context of transactional analysis – and in this way the connections to other TA concepts are emphasised. This will make clear what was indicated in the second article: The concept of Psychological Games is a cornerstone of Transactional Analysis and brings together a variety of other concepts and ideas of Transactional Analysis – into the complex communication events of Psychological Games.

Questions, suggestions and additions are – as always – welcome in the comments. Thank you very much!

Leave A Comment