Transactional analysis in conflict coaching

Summary

The second part of the trilogy on transactional analysis and mediation presents TA concepts based on conflict coaching. Using a dispute between brothers as an example, the possible Course of a conflict coaching based on transactional analysis presented. Both Eric Berns eight interventions as well as other concepts of transactional analysis. It becomes clear that transactional analysis provides a suitable set of tools for diagnosis and intervention when dealing with conflicts - whether in coaching or mediation.

Introduction

In this article on transactional analysis and mediation, individual concepts and models from the field of transactional analysis are presented. In order to emphasise them, they are not presented in the context of mediation, but in the context of conflict coaching.

Coaching is the counselling support for overcoming a sometimes problematic situation that needs to be developed. In conflict coaching, the coaching occasion is a conflict situation of the client that regularly presents itself as problematic from the client's perspective.

Possible questions and topics of conflict coaching can be, for example, how to deal with a conflict, to what extent something and what needs to be done and how to deal with the tensions, both emotional and social, until the conflict is resolved. The way in which support is provided depends on various factors, in coaching on the field of work, the occasion as well as the counselling approach and philosophy. What this means for the transaction-analysis-based approach will be the common thread running through this article.

Context of conflict coaching with TA concepts

Since the 1960s, transactional analysis has developed from therapeutic contexts into the entire field of counselling and education (Stewart/Joines 2016). In its therapeutic origins, it was designed to heal sick patients, but from the very beginning it utilised individual therapy in groups. In this respect, transactional analysis always focusses on the individual with their striving for autonomy, which they have to shape in their social contexts. In the sense of transactional analysis, a person is autonomous to the extent that they attain or activate awareness, spontaneity and the capacity for intimacy (on the concept of autonomy in TA Weigel KD 01/2017, 39; excerpt: Weigel 2014, 79 ff. Weigel 2014, 79 ff).

Both starting points - Shaping autonomy (individuality) in the social sphere (sociality) - define the thematic framework for both coaching and mediation. In both cases, the focus is on personal and self-responsibility in social relationships.

On the one hand, the article aims to provide an overview in order to capture the multitude and richness of transactional analysis concepts; on the other hand, however, its depths must also be explored. In view of the limited space available, the following approach offers a (good?) way out: on the basis of a roughly sketched problem case, the process-guiding TA concept of Berne's Eight Interventions A basic roadmap of transaction-analytical counselling will be used. This will make it possible to view further TA concepts along the way and present their main features. However, as is the nature of such "overland journeys", at best only a brief glance, so to speak, is possible. An insightinto the respective concept at the edge of the carriageway. The further (literature) references may help the interested reader to comprehend the prospects of this "rollercoaster" at their own speed (for comprehensive information, see the handbook TA in Mediation, 2014).

Example case

A client comes to coaching with the concern that he doesn't "know what to do with his brother" and wants to clarify what he can do and whether a conflict resolution process such as mediation, which is talked about everywhere, might help. He is in a "fierce and long-running" conflict with his brother. It is almost impossible to understand what the actual cause is. The atmosphere is fundamentally disturbed. In principle, the brothers have nothing more to say to each other, but at family celebrations things escalate time and again. The main problem now is their parents' impending need for care. This makes it even more difficult to avoid each other. As if their shared past, in which the two brothers had developed "completely differently", wasn't already problematic enough. What can be done, the client asks in general - and despairs.

Overview

Berne's eight interventions

Early on in the development of transactional analysis, Eric Berne described eight (therapeutic) techniques that he saw as having an inner logical order and which he emphasised as a whole (Berne, 2005, p. 207 ff). They are still regarded today as an important inventory of interventions in the transactional analysis methodological toolbox. Although they were formulated by him in the context of a group therapy setting, they are not limited to this (Schlegel, 2011, p. 295). Similar to the phases of mediation (see Kessen/Troja 2016 for details), they ideally describe the process of (individual) counselling, but can also be repeated or abbreviated.

However, Berne later emphasised that the most important intervention of transactional analysis is the Permission is. However, this was only later introduced into TA by his "pupil" Pat Crossman (TAB selected 1976, 25; cf. Berne 2001,154, "therapeutic main instrument of the script analyst").

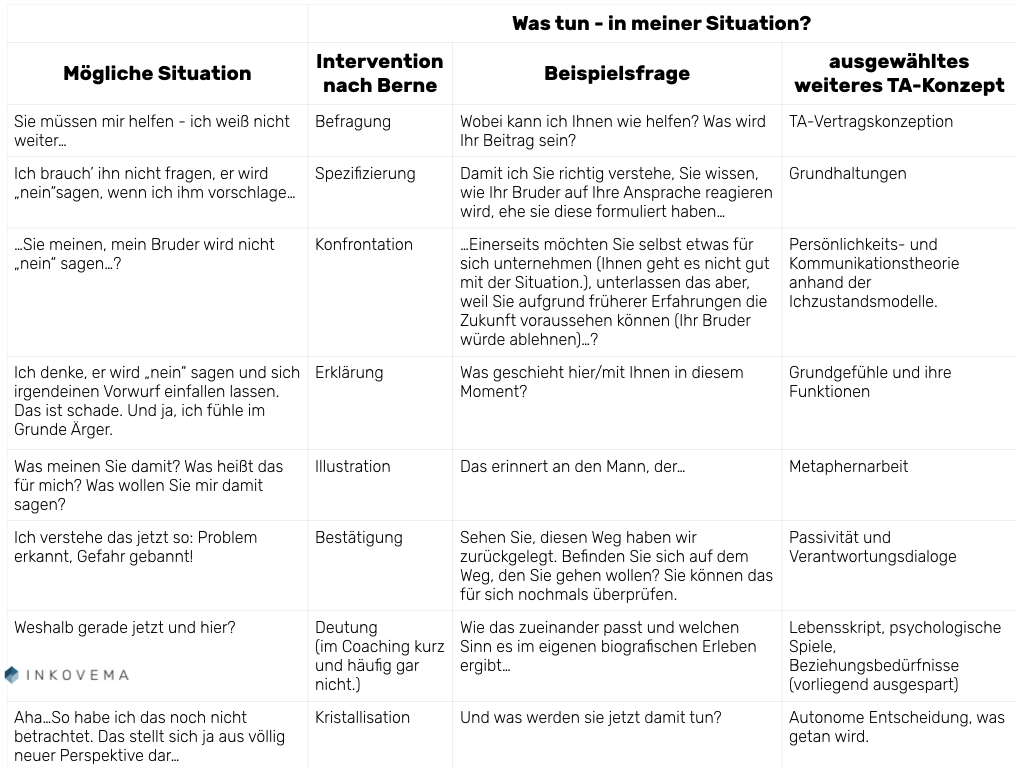

In the following, the eight interventions originally formulated serve to structure conflict coaching. Further TA concepts are presented below in line with this structure. For this purpose, examples of questions that may arise in a corresponding conflict coaching programme are presented (see table).

1st survey

On the one hand, interviews serve the coach to obtain information and, on the other hand, to "tap" the client's imagination, to stimulate him to search processes and often to provoke him slightly. They also give the client an indication of the direction the coaching will take (Berne, 2005, p. 207). This applies at least to the constructivist-influenced counselling approaches.

Of course, conflict coaching begins with a concrete clarification of the assignment: each party clarifies with the other what they can expect and whether and under what conditions the joint work will continue. In transactional analysis, the Concept of the Contract work (throughout the entire coaching process). This is understood as a process-orientated approach that aims to ensure that both sides know at all times what they are both working on. This special focus on the administrative, organisational and psychological level of the contract process serves to activate or maintain the client's personal responsibility. The coach uses this instrument to protect himself from worrying about the solution to the issue and contributing "more to the problem solution" than the client as the problem bearer. In this way, transactional analysis emphasises the conscious handling of framework conditions, target agreements and the psychological shaping of relationships (Schneider, 2002, p. 11). Transactional analysis is therefore primarily described as contract- and decision-orientated (Schlegel, 2011, p. 164).

This prevents the coach and client from getting lost in the "maze of communication" (Gührs/Nowak) and in the end nobody knows who contributed to what, that the client did or did not do something or that it was simply "just good to have talked about it". On professional contract work (exfrl. Nowak, 2014, p. 125 ff.; Hagedorn, 2014, p. 105 ff.; Gührs, M./Nowak, 2014, p. 45 ff., Weigel, 2012, p. 337 ff.) includes for transactional analysis that it

- is voluntary,

- both sides take responsibility for the content,

- the roles and tasks, competences and responsibilities are conscious and clear on all sides,

- reveals and clarifies unrealistic expectations ("The coach has the solution – and will give it to me!"),

- excludes unconscious manipulation,

- offers a roadmap for the coaching process and at the same time

- The focus is on the future and the necessary willingness to change.

Contract work therefore not only takes place at the beginning, but extends throughout the entire counselling process and is used iteratively. It corresponds most closely to the mediative approach by means of communication rules and situation-related agreements between the participants, which are concluded as required. From a systems theory perspective, contract work begins with metacommunicative questions or invitations (such as "What are we currently working on?"). The ability to metacommunicate (see Duss-von Werdt, 2016, para. 44) is practically the prerequisite for transaction-analytical contract work.

In doing so, the TA contract concept three levels, the administrative level, which covers the organisational framework conditions, the content/professional level, which formulates the work assignment and the mutual work contributions as well as the psychological level, which takes the unconscious parts into conscious consideration in order to prevent their otherwise disruptive influences (cf. Schneider 2002).

Contract work at the beginning of coaching aims, for example, to make the framework conditions clear to the client: the coach does not "have" to help, but accepts an "assignment", so to speak, if he is of the opinion that his competences are sufficient, his time allows it, the consideration is appropriate – financially, but also with regard to the client's problem-solving contribution(!) - and the coach is convinced that he can be of help to the client.

2. specification

Specifying is emphasising the essential content that the client has communicated. Firstly, it makes it clear to the client that they have been understood. More important, however, is the possibility for the coach to generate information in this way. The aim of both paths is to mark certain information so that it can be referred to later (Berne 2005, p. 207 f.). Further (transaction-analytical) explanations are prepared.

Specifications are added to the Paraphrasing resp. Looping in mediation (Kessen/Troja 2016, para. 30; Gläßer 2016, para. 26 et seq.), whereby it is not only the Mirror and reproducing what has been said as faithfully as possible, but rather emphasising what is – relevant from a counselling perspective. In this form, it is not just a Rapport-creating instrument, but a tangible, effective intervention (Gläßer 2016).

In the example case, the client will begin by describing failed attempts, which are intended to underpin the fact that further well-intentioned attempts will also fail – and increase their own despair. Corresponding emphasisations focus on the – meanwhile solidified – basic attitude of the client towards his conflict partner (brother). Statements and moods in this regard are emphasised because the coach assumes that this (internalised) basic attitude in the conflict would torpedo any further de-escalating conflict management aimed at cooperation. Unless the basic attitude "I'm ok. You are ok." is not stable and actively present in conflict management, constructive and co-operative conflict resolution will remain problematic. The fundamental concept of basic attitudes (see Weigel KD 01/2017, 40; Vogelauer 2014, 163 f.) can therefore be used explicitly early on in the coaching process and often proves to be easy to connect with. It is also an excellent way of focussing on the actual area of influence in coaching: The client's actions.

3. confrontation

In transactional analysis, an intervention that points out a contradiction in the client's statements is called confrontation (Berne 2005, 208 f.) What is significant about this is that it is not about a contradiction between a social norm and the client's actions or intentions; confrontation is not a rebuke, not an authoritative response by the counsellor. Rather, only the client's statements and information, his values and wishes, considerations and judgements - obtained through questioning - are used for a confrontation. This is the transactional-analytical way of reflecting, thinking, realising and re-sorting.

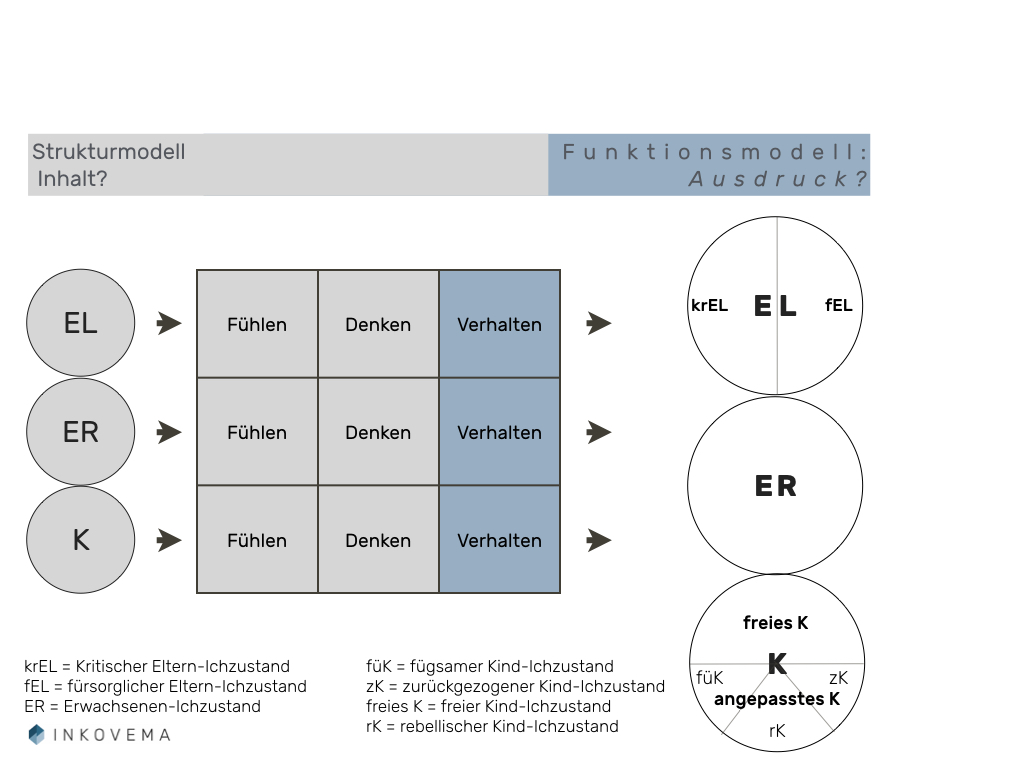

Such contradictions in the client's "inner system" arise primarily from the different dimensions of our personality traits, a complex field of tensions that mediation attempts to approach, for example, with its concept of positions and the underlying interests. Our positions and interests are by no means monolithic, stringently logical or free of gaps and contradictions. We want so much and believe we need even more. Transactional analysis, for its part, approaches this topic with its Concept of ego statesas she calls the different personality traits (Hennig/Pelz 2002, 27 ff., Schlegel 2011, 93 ff.).

The Ego state theory of transactional analysis is a broad, sometimes controversial field and is subject to new differentiations, sometimes structured research and, above all, graphic theory extensions in line with TA considerations, which seem impossible to present comprehensively here. For the present context, the basic differentiation into three ego state categories is important: Parent ego state, child ego state, adult ego state. Based on this differentiation, it is possible to name inner tensions and conflict situations, indecisions and contradictions in coaching and to organise them communicatively. And reflective communication based on these differentiations (further) trains an inner observer and forms personal responsibility, because own answers to contradictions and personal questions can be found. This is what TA methodically promotes if it wants to enable autonomy.

In theory, the Interface of personality and communication theory, from Structural and functional modelAlthough there are more than a few inconsistencies, contradictions and inadequacies (introductory ZTA 2015, 318 ff.; Mohr 2017; Mohr ZTA 2009), this is hardly a problem for counselling tasks that are already practically oriented. It may be pointed out here that it is one thing to scientifically prove the benefits of counselling and to scientifically substantiate counselling. In a science-orientated society, this is more than understandable. However, it is something else (and nonsensical) to want to answer moral and ethical questions on a scientific basis.

(Excursus: Science cannot answer ethical questions, but provides a framework for answering them. Even science is not ethically unprincipled, and is influenced by ethical fashions and myths in order to empower society.öpossible. However, this does not discredit it as an important decision-making aid. Nevertheless, it cannot justify ethics and therefore decide ethical questions. With its methods, science can sometimes prove whether certain facts are actually fulfilled in the chosen way. It can thus uncover internal contradictions of a certain ethic (e.g. by measuring), but it cannot recommend ethical alternatives for life (together) on its own (Harari 2015, 334 ff.; Harari 2017, 257 ff.).

Using the functional ego states, transactional analysis not only modulates its communication model between people, but is also able to depict "inner dialogues" that put people under tension. The following table provides an overview of the functional ego states of transactional analysis (see also Mohr 2014, 211).

In conflict coaching, parts of an inner dialogue alternate between self-accusation and accusation of others. The client alternately berates his brother and himself. It is not uncommon for statements to begin with why the brother "behaved impossibly" and end with self-reproaches for having lost his temper too early – or too late and thus having "been too lenient again". In the search for simple and explainable causalities that are supposed to tell a plausible (conflict) story, the individual approaches block themselves in their contradictions.

4. declaration

Contradictions can be explained. Initial approaches for conflict coaching based on transactional analysis arise not only from the social conflict, but also from the "personal conflicts" in coaching, the contradictions and tensions that are uncovered, which are associated with the different personality dimensions - and which are generally introduced, actualised and intensified in the social conflicts, especially in family conflicts. From a transactional analysis perspective, it is possible and obvious to use the functional ego states to "relate“ the inner dialogues" (see Gührs/Nowak 2014, 140 f.; Berne 2001, 417 f.; Hagehülsmann/Hagehülsmann 2001, 42 ff.) and in this way to introduce them into the social communication between coach and client for a reviewing reflection.

In transactional analysis-based coaching, explanation as an intervention means using a TA concept to stimulate the adult ego state by activating a here-and-now problem-solving orientation in order to reflect on the problem situation. Conflict-effective assumptions, beliefs and learnt certainties, i.e. contents of the (structural) parent or child ego state, are examined and considered, evaluated in the current light and, if necessary, adopted (Berne 2005, 209). Transactional analysis refers to such clarification processes as de-clouding or even re-decisions. This "strengthens" the adult ego state, making it more present and stable in social experience.

In the example case, it is conceivable that the client is struggling with his inner contradictions. He bases his assumptions and prognoses on old experiences, forms certainties from them and feels accordingly, e.g. sad, depressed, cramped. He does not dare to invite his brother to mediation because he fears rejection and new accusations, etc. And all of this seems within the realms of possibility.

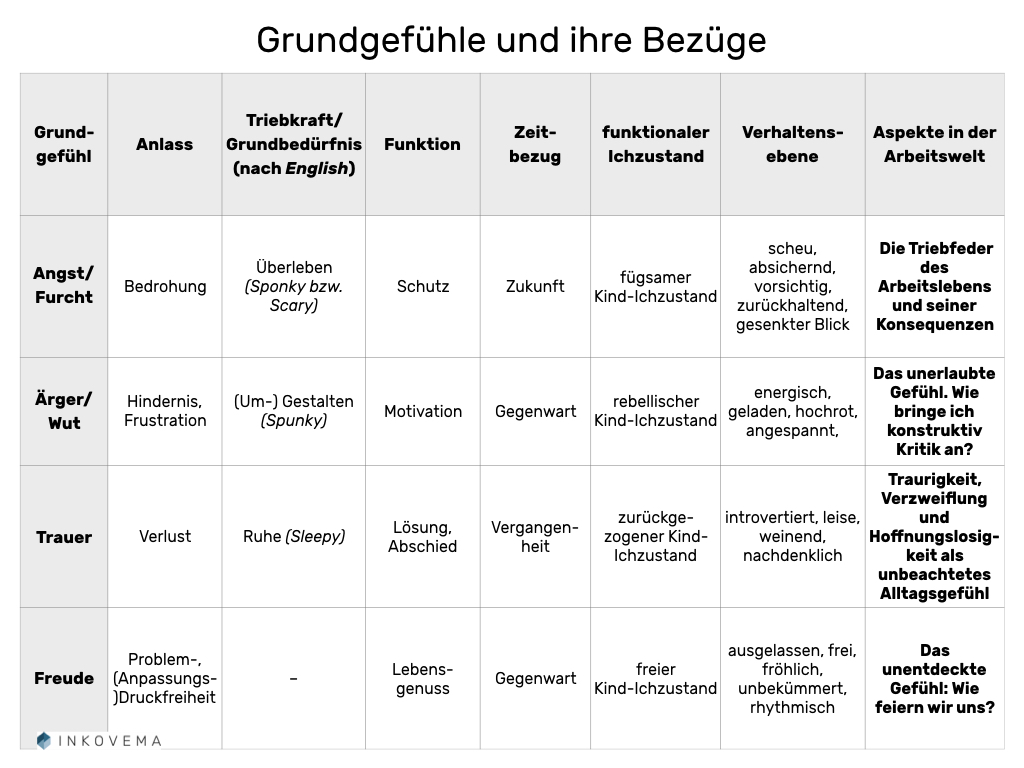

In addition, a feeling that would be perfectly justified does not appear in the communication: anger that his brother is or could be ignoring him in his desire for clarification. Classical transactional analysis conceptualises anger as a basic feeling and assigns it the function of mobilising energy in order to overcome resistance and obstacles outside of oneself. Anger is a personal energy supplier or rather an energy activator, a mobiliser that helps to put problems aside. Instead, however, the client may present dejection and rather feel sadness, the feeling whose function is to be able to say goodbye.

Here the coach could "turn off" and continue working with the concept of substitute feelings. This is an original TA concept. The concept of substitute feelings originated with Eric Berne himself. It was fully formulated and theoretically substantiated by the American transactional analyst Fanita English (2001), whose psychoanalytical background is very clear here. It is about the social character of feelings, which not only develop out of themselves, but also represent a social learning process. We feel, as the idea could be summarised, what others have taught us to feel or what we have learned to feel in the presence of others.

In the meantime, the concept of basic feelings will be followed. It serves to clarify the functions of feelings and to offer a sense-making effect. What this means in concrete terms can be seen from the following overview, which outlines a concept of basic feelings and their relationships in tabular form (excerpt: Thomson ZTA 1989; Oller-Valley 1989). Thomson ZTA 1989; Oller-Vallejo ZTA 1987; Schneider ZTA 1997, Weigel 2012, 445 ff.).

Of course, it remains crucial for the progress that the basic feeling of anger has a motivating effect, but rarely provides promising instructions for action. The misconception persists that the "authorisation" of a feeling also grants or entails the right to any form of expression; "I feel, therefore I may..." – Especially in conflicts, this assumption is a driver of escalation.

Anger has the function of motivating and providing energy, but the social modelling and concrete formulation is better an act of socially oriented awareness in order to make the speech inviting and connectable. In other words, anger can come across as repulsive and off-putting, but it can also be a social opener and socially orientated communicator.

5. illustration

Illustrations serve to visualise, using the power of confrontation and explanation by way of comparison to reinforce the desired effects or mitigate any side effects. In a sense, the transactional analyst adjusts his messages when he recognises from the client's reactions (feedback loop) that his explanations have scatter effects. For Berne, an illustration is more than an intervention such as questioning, specification (emphasising), confrontation and explanation. The illustration is a Interposition (Berne 2005, 210; Schlegel 2011, 299). In a sense, the transactional analyst pushes them between the client's previous and new, but unstable perspective. In this way, a mental back door is closed and - to stay with the metaphor - a foot is held in the newly opened door. The aim is to prevent the client from falling back into their old ideas. In practice, this is often done using a parable, an anecdote or a suitable metaphor (the mediator Watzke 2008 is a master of this).

For this example, several anecdotes naturally come to mind that not only stimulate the adult ego state in their humour, but also involve the child ego state. In this way, the central feeling of anger can be used as a motivating factor to actively approach the brother. In this way, unproductive ego states that are determined by self-pity and self-righteousness, for example, can be "pushed back".

The client could think that his brother is just waiting for him to "give in". This fantasised triumph of the brother could prevent the client from approaching the brother in an inviting and "unbiased" manner. This may be reminiscent of "the drunk", as reported by Berne (2005), who sat outside the front door in the freezing cold and would freeze to death after ringing the doorbell in vain and being asked why he would not try ringing again. The drunk man replied: "Let them wait!".

Perhaps this story by Watzke (2008, 146) would also fit quite well: An angel and a devil wander invisibly on earth. As a person passes by, the devil drops something. The human bends down and picks it up with great joy. "What have you given him?" the angel asks the devil. "A tiny piece of truth," says the devil. "What, you're giving people truth? I don't hear you, your job is to lure people towards hell and damnation." "So did I," replies the devil, "because I gave this person a tiny piece of truth and made him believe that this is the whole truth. "However the situation is illustrated, the idea is for the client to at least consider the obvious conclusion: To seek direct communication, in a questioning, interested attitude, ready to present himself and his "inner worlds" as well.

6. confirmation

The confirmation confirms the client's perspectives and insights. Their starting point is a newly acquired clarity and inner freedom from tension, but they are by no means routine. Moreover, these are merely new perspectives; the old ones have not necessarily disappeared or become irrelevant. Especially as they also contained their spark of truth.

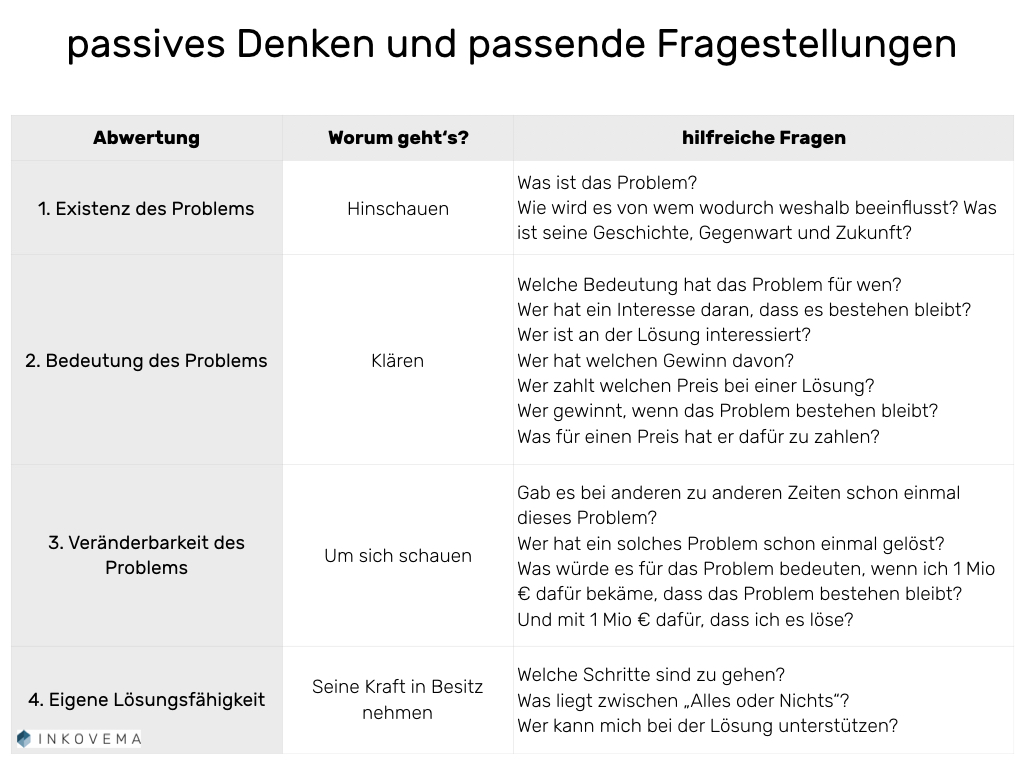

Depending on the situation, a review phase may be appropriate in the context of conflict coaching, which can have a confirming effect, but should at least avoid going astray. The transactional analysis concept of passive thinking is suitable for this.

Passivity is defined in transactional analysis as terminus technicus used. The concept has its origins in the so-called cathexis school (Schiff 1975, 1979) and describes the way in which people do not solve their problems, or at least not effectively. Passivity here means that nothing constructive is done to solve the problem. A distinction is made between passive behaviour and passive thinking. For the present context, only passive thinking is of interest.

Passive thinking means that information is unconsciously not taken note of and actively utilised, even though this would be possible and necessary for solving the problem. This omission is in the service of maintaining the current frame of reference (see Hennig/Pelz 2002, 192 ff; Stewart/Joines 2016, 272 ff).

Passive thinking has four different degrees (levels):

- the Existence of a problem is denied, not recognised,

- the Significance of the perceived problem is contested/played down,

- the General solvability of the significant problem is disputed and

- the own abilities to solve of the generally solvable problem is disputed.

The actual solution to the problem only begins once these steps have been taken. Only after leaving the stages of passivity do the mental spaces for creating solutions appear. Passive thinking itself walls off these spaces and makes them small and invisible. Only after leaving the passivity levels can "the" problem be viewed appropriately and dealt with by activating one's own possibilities. Passivity-orientated coaching is aimed directly at taking responsibility and consistently leads to dialogues of responsibility (see Schmid, KD 2012, 132 ff.; 270 ff.).

In this case, the stages of passive thinking could be used to evaluate the intermediate results.

- What is the real problem? Not that the brother is behaving so impossibly or has behaved so impossibly in the past, but that the client himself wants a change and is angry about the current relationship status and brotherly quarrel.

- How significant is this problem? Considerably, because there are always loud arguments, which are by no means interspersed with bonding phases. It is the only way they interact with each other. As a result, the client feels extremely annoyed, left alone and disturbed. The client recognises that the way he has dealt with his anger up to now has played a destructive role in the current situation.

- Is the problem generally solvable? A generalisation seems difficult here, but other siblings have been able to reconcile themselves with their difficulties. However, this perspective does not capture the client's problem. It is not about the sibling dispute as such. This cannot be dealt with in coaching. Instead, the focus here is on the client's problem.

- If the client's own problem can be solved in principle. Anger about the current situation can motivate them to initiate a satisfactory way of dealing with each other. If these attempts (to be planned) fail, it is important to recognise this and let go of the idea that something can be constructively changed in the unsatisfactory situation now or in the near future. This may then be disappointing, but it brings more agreement with the (reviewed) reality and ultimately sadness that a pleasant, unifying relationship is not possible. This leads to a redefinition of one's own situation: How do I deal with my grief situation?

Summarising Overview with practical questions:

7. interpretation

Before the goal of the coaching and the content of the contract crystallise, it is possible, although by no means necessary, to interpret life-history or model-related. Interpretation as intervention reveals the psychotherapeutic origins of transactional analysis. For this reason, the interpretation is only mentioned here for the sake of completeness and presented as a complementary option. It will be appropriate in more intensive coaching processes in which life history issues have also been dealt with in the necessary depth. This should not only be the case in coaching processes based on transactional analysis.

(Excursus – Brief references must suffice. In cases with biographical depth, the Concept of the life script (see Berne 2001; Schlegel 2011, 22 ff.; Peters 2014; Schmale-Riedel 2016). Also helpful are the Needs concepts of transactional analysis. In addition to basic physical needs (food, clothing, shelter), Berne has already identified basic psycho-physiological needs (stimulation, structure, strokes = affection). The need for structure is primarily concerned with the question of how time is spent as everyone moves through life. In this context, the well-known Concept of psychological games (see Berne 2003; Gührs/Nowak 2016; Nierlich 2014 for mediation). Also helpful is the Concept of relationship needs ("relational needs") formulated by R. Erskine, J. Moursund and R. Trautmann (Erskine ZTA 2008; adapted for mediation by Küster 2014). In terms of content, it builds on the Bernese starvation concept and emphasises the social needs of people. The approach is explicitly relationship-orientated and is therefore also well suited to mediation and conflict resolution processes in individual settings.

8. crystallisation

Transactional analysis is not only contract-orientated, but above all Decision-orientated. The The concept of decision is inherent in the central concept of autonomy (Weigel, Konfliktdynamik 1/2017, p. 39). In transactional analysis, we don't just analyse and "talk about it", we always work towards decisions, towards consciously shaped actions or omissions. This idea already appeared in the contract concept and now leads to the end of the intervention chain: the Crystallisation. It is the "technical" goal of transactional analysis - also in conflict coaching.

Crystallisation is the situation initiated by the coach in which the client is faced with a decision-making situation. It is the consequence of the "contractually agreed" coaching work.

"And what are you going to do about your situation now, after everything we have looked at here? Which of the paths we have looked at will you take?" could be a question for crystallisation. It is crucial that the coach does not favour one direction, but rather makes it clear to the client that the coaching is coming to an end. The coach witnesses the client's autonomous agreement with himself one last time.

The coach makes sure that the client's productive ego states support the agreement and that the destructive ones are left out (see Gührs/Nowak 2016): Does the client consider their decision to be sensible and reasonable even in the face of the possibility of failure (adult ego state)? Do they feel the desire and pleasure to implement this decision in practice (child ego state)? Is the decision in line with their values and beliefs (parent ego state)?

Leave A Comment